Oscar Bluemner

Oscar Bluemner came to the United States in 1892 from Germany, and first continued an architectural career begun in Germany. By the 1900s, under the influence of the Modernist artistic circle of Alfred Stieglitz, he increasingly turned to drawing and painting, and gradually abandoned architecture.

An extended trip to Europe spurred a dramatic modernization of his style. Upon returning to the U.S., he took part in the Armory Show, the Forum Exhibition of 1916, the first Whitney Biennial and had solo shows in Stieglitz-sponsored galleries and elsewhere in New York City.

Although his work was well-received by critics, sales were poor, and he often lived in poverty. Anti-German sentiment prompted by World War I led him to relocate from New York City to New Jersey, where he repeatedly moved his family in search of cheap lodging. When his wife died in 1926, he went to live with his son in Braintree, Mass. and supported himself with assistance from the WPA arts project. In 1935, he was severely injured in an auto accident, and never resumed painting. His eyesight failing and in a deep depression, he committed suicide three years later.

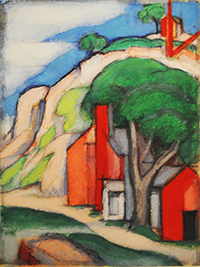

Bluemner painted a distinctive terrain of farms, factories and unkempt suburbs, which he described as "the intimate landscape of our common surroundings—the things and scenes most closely interwoven with the progress of life." His depictions of the industrial hinterlands of New Jersey and Massachusetts combined political and social sympathy for the workers who toiled there with the most modern artistic language. The characteristic touches of glowing red in his paintings and his interest in color theory earned him the nickname "The Vermillionaire." Strongly influenced by the Neo-Impressionists, he rejected their more scientific ideas in favor of more emotional and spiritual ideas about color. He once said, "I paint my attitude, I would be a composer, but being all retina, I saw it [his environment] all as color."

In the last quarter-century, Bluemner's significance has been recognized in several important exhibitions and new publications, and a steady succession of his works has entered major museum collections. He is now widely acknowledged as a key player in the creation of American artistic Modernism, taking his place in the pantheon alongside better-known colleagues such as Georgia O’Keeffe and John Marin.