‘Camera-Less Photography’ Exhibit Comes to Hand Art Center

“Camera-less photography?” That’s an oxymoron – a joke, right?

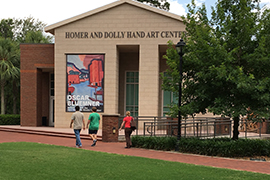

No. Proof of camera-less photos can be seen in “Image for Concept: Indirect Representation in Photography,” an exhibit at Stetson’s Hand Art Center that runs Monday, Jan. 13, through Feb. 8.

Another exhibit, “Garniture,” runs Jan. 13 through March 28 and will feature a “symbiosis” between the university’s collection of American painter Oscar Bluemner artworks, and wallpaper and textiles created by Madison Creech, MFA, visiting assistant professor in Creative Arts.

“Image for Concept” was created and curated by James Pearson, MA, who became the director of the Homer and Dolly Hand Art Center on Dec. 10. The exhibit features works by artists Bennie Flores Ansell, Bradly Brown, Amy Theiss Giese and Andy Mattern, who create camera-less photos by recording lights and shadows with light-sensitive photo paper.

“One of the main reasons I put this show together was to question people’s understanding of photography,” Pearson said. “Like no other art form, photography is extremely tied to the technology used to produce it, from the camera obscura thousands of years ago to today’s modern DSLR (digital single lens reflex cameras) and Photoshop techniques. I wanted to find people who are doing what can only be considered photography, but when you start to look at it, maybe it’s considered alternative practices. It’s investigating the difference between when does photography stop and it become image-making.”

As Pearson noted, camera-less photography is not some newfangled 21st-century technology, and it’s not any one single technology.

“The camera-less capture can come through various mediums,” he said. “There are a lot of ways to come to that image without using a machine.”

Pearson makes ample use of that word “capture,” as both noun and verb, to describe the works in the exhibit, a purposeful choice designed to subtly alert viewers that these artists are not “taking” or “snapping” photographs – they are, like alchemists of light, “capturing” images.

Archaeologists say that camera obscura effects were described in Chinese writings dating to the 4th century B.C.E. Using the natural properties of light, a camera obscura device consists of a box, tent or even a room with a small hole in one side. Light passing through the hole will cast an image, although inverted and reversed, on the surface inside.

Even as Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre invented the first publicly available photographic process, the daguerreotype, in 1839 – which utilized a camera – various non-camera techniques also were developed in the 19th century, Pearson said. In fact, works by multi-media artist Bradly Brown in “Image for Concept” are examples of cyanotype, a process developed in the late 1800s. Cyanotype uses an iron-based liquid, and the iron reacts to UV light from the sun.

To create a cyanotype, “You coat something, you put it out in the sun and it changes color,” Pearson said. “So now you can coat something, put things on it and then put it out in the sun, and you record that image of whatever you put on it. So technically it’s a lot closer to capturing a reality (than traditional camera photography).”

Brown’s captures include spiderwebs and, Pearson added with a laugh, “a pair of tighty whities” (underwear). The resultant prints – snow-white images on fields of cyan blue – spring from the same process that engineers once used to create blueprints.

Amy Theiss Giese, a professor of photography at the Institute of Art & Design at New England College, uses a different technique “to explore the root of capturing light on paper, which is kind of the basis of photography,” Pearson said. “Normally that’s the camera that fixes the image on the paper. What she does is bring photo paper into rooms, lays it out on the flooring and lets it stay exposed to the night lights over a period of 11 or 12 hours. So, it’s moonlight or sometimes it’s headlights flooding through the windows. Any light of the room is recorded. So what you have is literally the record of the light that occurred in this spot overnight.”

Pearson is quite aware that some viewers will proclaim that the works in “Image for Concept” are not photography because they don’t depict recognizable everyday objects.

“My answer is ‘Why is it not photography?’ ” he said. “Is it in the capture? Is it in the composition? Is it in the digital editing afterward? Is it in the Polaroid where you don’t get to touch it at all? I would actually question their understanding of the medium because it’s so diverse.

Pearson notes what he calls “this idea of Instagram reality . . . You go to Instagram and see these Instagram models or influencers caked with filters and makeup, and they shrink the size of their waists and blow up the size of their hips, and it has no reference to reality at all.

“Especially in these days, we are so inundated by images in a world of fake news where we can’t exactly trust the things that are put toward us. I want people to leave the gallery space with a better understanding of the development of photography and capturing images from life, and maybe also with a healthy critical basis to engage other imagery — to better understand the world around them by saying ‘Maybe we should question the images that are in front of us.’ We have to now assume that images aren’t real until proven otherwise. Before it used to be the other way: This is an image – it must be true,” he said.

“Garniture” Exhibit

“Garniture” is a collaboration – what Pearson calls a “symbiosis” — between German-born American Modernist painter Oscar Bluemner (1867-1938) and Madison Creech, Visiting Assistant Professor in Creative Arts.

Bluemner exhibited in the renowned Armory Show in 1913 and the first Whitney Biennial, but he garnered little attention from his death in 1938 to the early 21st century. His daughter Vera Bluemner Kouba retired with her husband to DeLand in the 1970s, and upon her death in 1997, she bequeathed her collection of more than 1,000 of her father’s works to Stetson. The Hand Art Center presents various Bluemner exhibits on a regular basis.

For “Garniture,” Creech used digital technology to create wallpaper and textile designs inspired by Bluemner’s drawings and paintings. Creech holds an MFA in fibers from Arizona State University and a BFA and BS in textile, merchandising, and fashion design from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Creech cited the Wikipedia definition of “garniture:” “a number or collection of any matching, but usually not identical, decorative objects intended to be displayed together.”

Bluemner’s works, which will be exhibited in “Garniture,” “are a field guide to deciphering the imposing wallpaper and textile designs enveloping the walls,” Creech said. “I’m hoping guests will have the thrill of discovery, identifying elements of the wallpaper and textile design to the original Bluemner works. Maybe it will feel a little like bird-watching, ‘eye spy’ or digging through a thrift store looking for treasures.”

— Rick de Yampert

If You Go

“Image for Concept: Indirect Representation in Photography” runs Jan. 13-Feb. 8. “Garniture” runs Jan. 13-March 28, with a reception 6-8 p.m. Friday, Feb. 21.

The Hand Art Center is located on Stetson University’s Palm Court, 139 E. Michigan Ave., DeLand. Admission is free and open to the public. Designated parking is available in the lots at East Arizona Avenue.

Center hours are 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday through Wednesday and Friday; 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Thursday; and noon-4 p.m. Saturday.

Closed on national holidays and holiday weekends. For information, call 386-822-7270 or visit https://www2.stetson.edu/hand-art-center/