Our Vanishing Shoreline

by Jason Evans, Ph.D.

While at New Smyrna Beach over a recent holiday, I watched my wife and son play in the sand and surf. Of course, the husband and father could enjoy this happy moment, but the scientist in me feared what the future holds for our vanishing coastline.

As a Central Florida native, I know the beauty, splendor and economic importance of our coasts. Sandy beaches, bountiful estuaries and mild subtropical winters have attracted visitors from all corners of the world. Many of these visitors inevitably return to settle, leaving behind cold winters and creating new lives in their own little piece of paradise.

For my family, this process began with my paternal grandparents, who first moved to Central Florida in the early 1960s. Transplanted from Baltimore, they settled into a modest new house on a small Orlando lake.

Like many who grow up here, frequent trips to Daytona Beach became a staple of my dad’s childhood. This tradition continued straight into the next generation with me, my sister and various cousins. Hot summer days spent at the Daytona Beach pier with cars packed with people, food, various beach toys, and without fail, piles of fugitive sand on the car seats.

These wistful experiences are an indelible part of my own childhood memories.

When I reflect on my current research into the rising sea level, memories such as these inevitably turn up with a mixture of loss, nostalgia and — perhaps most strangely – hope.

As a teenager, I remember going to Daytona Beach for a Memorial Day visit and viscerally realizing that the amazingly wide beach of my earlier childhood (really only a few years before) was merely a fraction of what it once seemed.

Perhaps, I first thought, this was an illusion of growing older. My parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles agreed that the beach indeed seemed much narrower than it used to be. More worrisome, my family members concurred that this narrowing of the beach had been happening for some time and by my grandpa’s sage reckoning, was “fast getting worse.”

“What happened to our coastline?” my family wondered. We did track a lot of beach sand into our cars but not that much. It became obvious that other — far more important — factors caused the rapid loss of Daytona Beach.

Some of these factors are, in a sense, quite natural in origin. For one, environmental scientists have long known that sandy beaches like those at Daytona are changeable places. Tides, storms and winds inevitably move the beach around over time, often making barrier islands.

Therefore, erosion of a beach is not all that new or surprising.

Of course, this natural process of erosion still causes alarm, particularly if the ocean begins to claim your beachfront building or property. The many miles of protective sea walls and other engineered barriers along our developed coast mark the ongoing battle to protect human investment against the sea’s erosional force.

Such sea walls, however, exact an ironic toll, since stopping the erosion at the face of the sea wall speeds it up elsewhere. This often results in more rapid loss of the beach itself.

Truth be told, the sea walls near the Daytona Beach pier likely played a major role in the rapid loss of beach I observed as a teenager back in the early 1990s. In fact, many beach communities along the east coast of the United States have grown wise about sea walls and instead have patiently cultivated and restored large sand dunes. These are little vegetated hills of sand on the beachfront between the ocean and human development. My favorite example is the City of Tybee Island, Ga., which over time has covered a 1930s-era sea wall with a vegetated dune field that in some cases exceeds 20 feet above sea level.

But how I wish the problem was as “simple” as better management of coastal erosion, or as straightforward as replacing ill-conceived sea walls with semi-natural sand dunes. In fact, long-term measurements indicate that sea levels along the east coast of Florida rose about seven inches between the years of 1900 and 2000. This may not seem like a tremendously large amount of sea level rise, and, in fact, sea level rise was until recently not viewed as a major concern in the development of Florida’s coastal communities. However, large amounts of research indicate that the seemingly modest rate of sea level rise in the 20 century had not been seen on Earth since near the end of the last ice age.

In other words, we now know that the rising seas of the 20 century are among the earliest indications of human-caused climate change, correctly known as “global warming.”

More recent measurements suggest that the sea is now rising about 1.3 inches every 10 years. That’s almost two times as fast as that observed during the 20 century.

The best scientific projections of sea level rise for the year 2100 range from a “stay the course” scenario of one foot, all the way to what I call the “doomsday” scenario (think rapid melting of Greenland and West Antarctica) of more than six feet.

Whatever the scenario, it’s important — if sobering — to remember that most climate scientists do not expect sea level rise to end by 2100, but instead project for the sea to continue rising many centuries into the future.

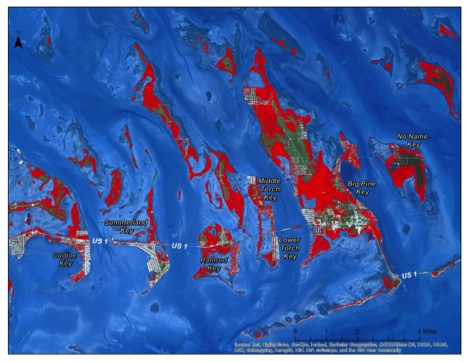

It is, frankly, almost too easy to create maps showing what any part of the Florida coastline might look like under six feet or, taking the long view, even 100 feet of rising sea level. The beaches we now know would lie far underwater, along with vast swaths of coastal real estate that we could no longer afford to protect. Low-lying freshwater and forest ecosystems would slowly give way to saltwater tolerant mangroves and then to open saltwater lagoons and oceanfront beaches.

Sitting atop the DeLand Ridge, the area around Stetson University eventually becomes an island, perhaps with a climate not all that much different from today’s Florida Keys.

The scientist in me can attempt to rationalize such scenarios. For example, the limestone of the Floridan aquifer beneath us, which is the source of our drinking water and blue water springs, serves as testament that Florida was once under the sea before.

What matter, one might ask, that it may be destined to do so again?

But maybe it’s only natural that my scientific objectivity is quickly overridden by my deep emotional connection to this special place. Indeed, trying to make sense of what any of this means, even within our own human time frames, is one of the most daunting tasks faced by educators and researchers in the environmental sciences.

That meaning became clear yesterday as I watched my wife and three-year-old son giggling in delight as the gentle waves rolled up the New Smyrna Beach sand. Dolphins, pelicans and terns feasted on baitfish in the dusk light, no doubt finding joy and nourishment in the moment. I turned once more to look at the six-foot-tall sea wall behind me, wondering, just for a moment, if some other father 200 years from now will be able to stand in this very place watching his son.

For no reason that I could describe as scientific, in that moment I felt hopeful that we as a human community will indeed come together and take the steps needed to halt the rising sea.

Jason M. Evans, Ph.D., is assistant professor of Environmental Science and Studies at Stetson.

Top photo is by Robert Sitler, Ph.D., Stetson professor of Modern Languages and Literatures, for his project titled “Aquatic Gems,” a look at our water wonders within a 30-mile radius of Stetson’s fountain.