Learning to Embrace Diversity

We are not compelled to become blind to diversity, but to celebrate the richness it offers.

by Ronald Williamson

If people just get to know one another, they’ll understand one another better, work out differences and everything will be fine.

Sounds logical, right?

But it’s pure Pollyanna reasoning, scholars say. The off-base thought does, however, raise questions about higher education’s role in diversity and in fulfilling the promise of democracy.

“It’s a logical fallacy to think that if people just get to know one another, they will be ‘friends’ and everything will be all right,” says Shawnrece Campbell, Ph.D., associate professor of English and director of Africana Studies at Stetson University. She echoes the words of Ina Corinne Brown, a mid-20 century social anthropologist whose writings have influenced Campbell.

“The sober fact is that we have to learn to get along with people who are different and likely to stay that way,” said Campbell. “The role education plays in diversity is directly related to its ability to help people get along, despite differences and regardless of personal feelings.”

Education can provide the essential face-to-face, experiential and philosophical engagement required to learn to get along with others in our incredibly diverse society, she said.

Learning Multiculturalism

Campus conversations about diversity, inclusiveness, minorities and multicultural issues heighten across campus every winter as Martin Luther King Jr. Day passes and Black History Month begins.

“Higher education helps prepare students to be multicultural citizens within a country made up of many diverse cultures,” adds Patrick Coggins, Ph.D., a Stetson professor of multicultural education. “The goal of multicultural education is to foster unity within this diversity.”

“We are one people,” he said, pointing to the United States’ motto, E Pluribus Unum or, out of many, one. The preamble to the United States constitution begins with “We, the people.”

The people. Singular.

The promise of democracy is “a pluralistic society that works,” says Daryl G. Smith, Ph.D., one of the nation’s most eminent diversity scholars.

It’s as simple as that, and as complex.

“Higher education has a role in building a pluralistic and equitable society, a society that thrives on diversity,” according to Smith, a senior research fellow and professor emerita at California’s Claremont Graduate University. Although diversity on college and university campuses is a reality today, she said, there’s more to be done if higher education is to help meet democracy’s promise.

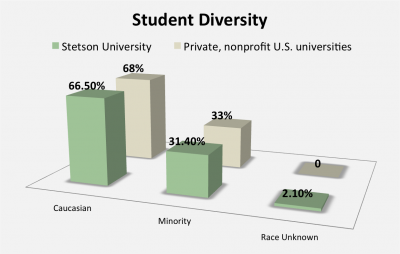

That reality at Stetson is encouraging.

Efforts here have resulted in more students from different regions of the country and the world, according to university figures. Undergraduates hail from 45 states and 52 countries. Since 2011, there has been a 61 percent increase in out-of-state students and a 42 percent increase in international students.

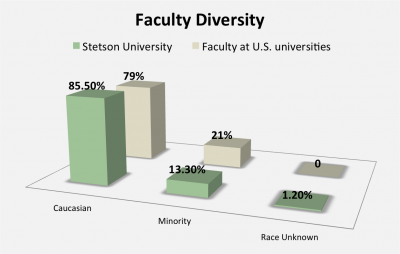

Stetson’s demographics are similar to those of the nation and ahead of the curve of its peer institutions, the studies show.

Faculty Diversity

“It is important to increase the number of minority administrators, students, and faculty to reflect the essential fabric of American diverse society,” said Coggins, “but that is just part of the measure of success.”

“We can boast about the numbers, but what about the attitude of the students and faculty?” asked Coggins. “Even though we invite diversity, we do not change our attitude to be accepting of making minorities equal partners.”

Coggins held a Jessie Ball DuPont endowed chair from 1991-2011 and has founded several campus organizations. His is a formidable voice for multiculturalism.

Hiring and retaining diverse qualified faculty is essential for inclusive institutions, Smith said, and has numerous advantages. But its broad and deep implications aren’t always easily discussed and this can hinder the task.

“In general, it is challenging to achieve demographic diversity, especially ethnic and racial diversity, in any academic search,” said Provost Beth Paul, Ph.D., vice president of Academic Affairs at Stetson. “Layers of educational and social disparities have ensured a slow pipeline into academia for faculty and staff of color.”

According to Smith, the key question for each institution is this: what expertise and talent is needed, today and in the future, to be credible, effective and viable in a pluralistic society for today and tomorrow.

“As many fields in our society are still more homogeneous on certain demographic characteristics, yes, there are certainly faculty searches in which the candidates are skewed on various demographic dimensions,” Paul explained. “For example, more females than males apply for positions in education; more males than females apply for positions in computer science.”

Hiring and retaining diverse faculty can be difficult and, despite improvements, it continues to lag, said Coggins.

Some 83 percent of the nation’s teachers are white, middle class, English speaking and hold degrees from predominately white institutions, he said. Thus, they “have little or no experiential background for effectively teaching diverse students and the increasing immigrant populations.”

Building Trust

Because of that difficult situation, said Coggins, building trust has become a major challenge of higher education today, and that is done by addressing the situation head on and building a faculty of effective cross-cultural teachers who, among other things, realize the vast differences within minorities.

“One size does not fit all,” he said. “Effective cross-cultural teaching entails developing a certain personal and interpersonal awareness and sensitivities, developing certain bodies of cultural knowledge, and mastering a set of skills that taken together, underlies success.”

Educators also must build their cultural competence so they can relate to students’ cultural differences, value minority students’ intellectual competence and choose text books and materials that are culturally connected to diverse students.

The benefits of faculty diversity go beyond teaching, Smith said.

A diverse faculty is essential to the institution in decision-making and in vital relations with diverse communities near and far. They also provide role models for undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs and faculty. They attract persons from diverse backgrounds and develop diverse forms of knowledge.

“The notion that all minority faculty are able to adjust to institutional norms without any trouble is unrealistic,” Coggins said, noting that retaining minority and women faculty through the tenure and promotion process is a problem for most institutions. One way Stetson has increased its retention of minority faculty is by providing them with mentors to guide them through the processes of advancement.

“Stetson University has worked diligently over the last several years to use effective strategies for attracting and considering diverse candidates,” said Paul. “These efforts are achieving more diverse candidate pools and the subsequent appointment of a more demographically diverse faculty. Attracting, appointing, and supporting diverse faculty is a strong university commitment.”

But while there are many immediate concerns and improvements to make, Smith is already concerned about the future.

“We are at a critical juncture for diversity efforts,” she warns. We must look beyond strides in admissions and curriculum diversity, and build capacity on an institutional level, in all its dimensions, to support and sustain the progress that has been made.

“Building institutional capacity is an imperative,” Smith said recently, “The future viability and health of a pluralistic democracy will depend on it.”

Mission Centric

Institutions must “set diversity at the center of their mission” and make it as fundamental as technology, according to Smith They must engage in difficult and ongoing dialogues, at all levels of the institution, about the challenges of how to support and sustain their missions in the future, similar to the way institutions have done for decades with technology.

Stetson’s mission and values statement commits not only the university, but also individuals, to “community engagement, diversity and inclusion, environmental responsibility, and social justice.”

Stetson’s mission and values statement commits not only the university, but also individuals, to “community engagement, diversity and inclusion, environmental responsibility, and social justice.”

Efforts toward diversity in higher education are having an impact in society, said Benjamin Reese Jr., Ph.D., president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education and a professor of psychology at Duke University.

“Students who have a college or university experience where faculty and administrators pay deliberate attention to encouraging a broad range of perspectives in learning tend to place more value on diversity,” said Reese. These young people have studied with individuals from diverse backgrounds and experienced a range of perspectives and viewpoints.

“They tend to be comfortable in and even seek such environments as places to live and work,” he said. People getting along with one another, living and working together is a good sign that more people are learning to get along despite differences.

“That ability comes with time,” said Campbell. “It’s a lifelong process, not a one-and-done deal.” We must learn to recognize and avoid innate cultural stereotyping as well as the continuous stereotyping in music, newspapers, television, textbooks and a myriad of other ways.

“It takes interpersonal experience with the so-called ‘other’ to change the way people feel in their hearts,” Campbell said.

“You can have diverse inclusive campus programming everywhere, but never change the culture of the university campus itself,” said Campbell. “If students, faculty, and administrators of different races, ethnicities, religions, sexual orientations and such aren’t hanging with each other outside of the classroom, or having dinner at each other’s homes, going on vacations or other outings together and so on, the culture will not change.”