“Resistance of the Heart”: Holocaust Memorial Lecture recalls Rosenstrasse Protest

In 1930s Nazi Germany, public posters warned about “Rassenschande” – “race defilement.”

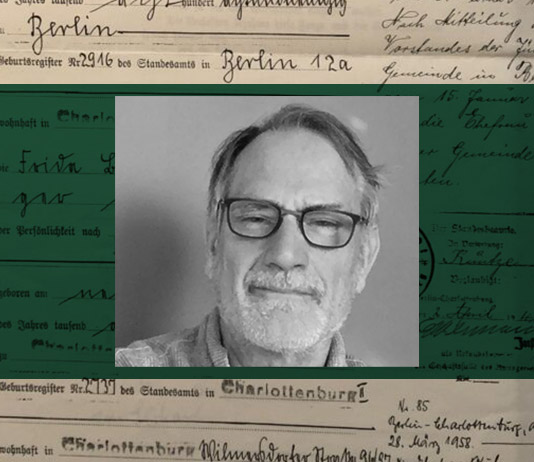

“These posters were saying you can be executed for sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews — racial purity is what the Nazis were aiming for,” said Nathan Stoltzfus, a Florida State University professor, as he presented Stetson’s annual Holocaust Memorial Lecture on April 7, both in-person at Rinker Auditorium and virtually via Zoom.

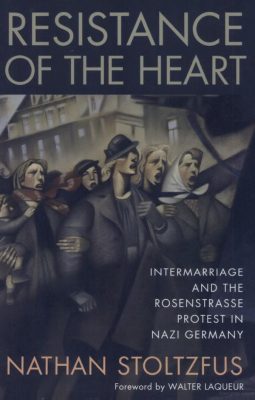

The lecture, titled “History as Reproach? The Nonconformity and Protest of ‘Mixed-Race’ Couples in Nazi Germany,” drew from his research and interviews of survivors in Berlin in the 1980s, which led to his groundbreaking and controversial 1996 book, “Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany.”

In February 1943, more than 2,000 intermarried Jews were detained at a center on Rosenstrasse (“Rose Street”) and were scheduled to be deported to work camps. In the only protest of its kind in Nazi Germany, the detainees’ non-Jewish partners, mostly women, spontaneously demonstrated for a week on the street outside the center. The Gestapo relented and most of the detained Jews were released. The wives’ actions became known as the Rosenstrasse Protest.

“Intermarried Jews were the most loathsome of German Jews to the Nazis,” Stoltzfus said as a slide of a Rassenschande poster was projected on a screen. “They were bad propaganda. They were a kind of union that no one wanted to admit. They didn’t prove Jews were so inferior that they couldn’t be in Germany. They committed racial treason.

“Looking at the survival of these intermarried Jews, the numbers were remarkable: 98 percent of ‘full’ German Jews who survived without hiding were married to non-Jews,” said Stoltzfus, who is the Dorothy and Jonathan Rintels professor of Holocaust Studies at FSU. “They survived because they were married to non-Jews. Why?”

Eric Kurlander, PhD, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of History at Stetson, introduced Stoltzfus by noting, “He is one of the world’s leading scholars of resistance to the Nazi dictatorship. Dr. Stoltzfus has helped redefine the field and initiate new debates and establish fruitful lines of inquiry. When he started doing his research in the 1980s, we had just started to look at nonconformity as something that wasn’t focused on outright resistance – military resistance or attempts to actually assassinate Hitler.”

Stoltzfus, Kurlander said, looked at “how relationships between men and women, including intermarriage, could be forms of nonconformity, and the ways that every day people tried to oppose the Third Reich in everyday life.”

Kurlander added that “Resistance of the Heart” was a co-recipient of the prestigious annual Fraenkel Prize for best book on the Holocaust, and that he uses that work in his classes on the Holocaust and Nazi Germany.

“As a graduate student in Berlin in the mid-1980s, I began asking scholars and survivors ‘Why did these German Jews survive, how do you explain that?’ ” Stoltzfus said. The explanative “narratives” he encountered — regard for the Aryan partners, such intermarriages survived underground, or it was sheer fortunate luck or even a “miracle” — “did not square with my image of the Nazis, and most importantly to me it doesn’t give credit to these remarkable and courageous women who were the agents of the success.”

Stoltzfus interviewed two dozen participants in the protests, and discovered their initial motivation “was not political, but totalitarian Nazi-ism’s insistence on regulating sexual relations in marriage forced them to become political.”

Stoltzfus said protestor Elsa Holzer told him, “ ‘If we had calculated we wouldn’t have gone to the street to protest. We acted from the heart and it’s surprising what you can do when facing crisis, how much strength you might be able to gain if you take the first step. We did not begin by thinking whether the protests would matter, but as the police repeatedly threatened to shoot us down in the streets, and as they didn’t do it, we began to get hope that maybe we will prevail.’ ”

Stoltzfus quoted entries about the Rosenstrasse Protest from the diary of Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s close aide and the Reich’s Minister of Propaganda: “The people gathered together in large throngs and even sided with the Jews to some extent. I will commission the security police not to continue the Jewish evacuations during such a critical time.”

One key to Goebbels’ action, Stoltzfus said, was that “the regime didn’t want people to know about these intermarried cases. They were embarrassing.”

Hitler and Goebbels did not see the release of the intermarried Jewish detainees as a defeat, Stoltzfus said, adding: “When Hitler compromised, he never compromised on his ideology or his goals – it was only a tactic.”

Yet the Rosenstrasse Protest departs from many “scholarly narratives of how the regime operated,” Stoltzfus said. “Many see it as a steamroller, ordering from Berlin what was supposed to happen, the subordinates following up, not improvising, not changing the letter of the law . . . .

“The intermarried paradigm was nowhere near the definition of resistance as postwar scholars made it. That was centrally organized, politically motivated efforts to overthrow the entire Reich. That’s not what this is. I call it a resistance of the heart,” he said.

The Holocaust Memorial Lecture, held in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day on April 8, was sponsored by Stetson Hillel, Stetson’s Jewish Studies program, and Stetson’s Program in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies.

— Rick de Yampert