Autograph of a Lifetime

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the Spring issue of Stetson University Magazine, available online.

“You can’t depend on your eyes when your imagination is out of focus.” — Mark Twain

My first visit to Hannibal, Missouri, was vicarious, made through the pages of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in the fourth grade.

What I didn’t know at the time was that Mark Twain’s real name was Sam Clemens, and he had based the book on actual settings, events and people from his childhood in Hannibal, where he lived from the age of 4 to 17.

“My favorite author” soon became “my favorite subject,” although I’ve never taken a class in Mark Twain studies. I discussed Twain with anyone who broached the topic of literature. My children warned their friends ahead of time: “Whatever you talk about with our mom, she’ll find some way to connect it to Mark Twain.”

Guilty.

My first actual visit to Hannibal was in 1996. Everything Twain had described in his writing appeared before my eyes: Jackson’s Island, the Mississippi River, Cardiff Hill, his boyhood home, the old cemetery and the Mark Twain Cave. Twain’s uncanny accuracy for details prevailed. Everything seemed familiar at once, even though this was my first visit.

Upon touring the cave with a dozen or so eager tourists, I was shocked to learn the cave contained some 250,000 signatures on its walls dating back to its discovery in 1819. Despite searching for years, the owners had been unable to locate a boyhood signature of Sam Clemens. It was easy to see why. With so many signatures scrawled throughout 260 passageways covering 3 miles, and only a small portion of the cave being lit, locating that boy’s signature would be an impossible task. Still, I had to try.

Hannibal soon became my favorite haunt, and I serendipitously became the executive director of the Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum in 2008. This provided the opportunity for many more excursions into the cave, always keeping an eye out for that elusive signature.

I became friends with Linda Coleberd, the owner of the cave, and she never denied me the opportunity to explore and search for Sam Clemens’ signature. She frequently joined me and even helped me host a special visit from country music superstar Brad Paisley with his boys, Huck and Jasper, and his father, Doug.

Although signing the cave was once common, the practice was eliminated in 1972. Linda, however, invited the Paisley family to add their names to the cave’s legacy. That was a fun afternoon!

I moved from Hannibal to become the executive director of the Mark Twain House & Museum in Hartford, Connecticut, but I still had many opportunities to visit Hannibal and the cave. I eventually moved back to Florida and became director of education at Epic Flight Academy, indulging another passion: aviation.

Hannibal still remained the constant on my compass, and I agreed to serve as events coordinator for Hannibal’s 2019 bicentennial. On each of my visits to Hannibal, I made time to wander through a few cave passages, reading the walls and looking for Clemens and Blankenship. (Tom Blankenship was Sam’s boyhood friend who became the model for Huckleberry Finn. So, naturally I look for his name, too. Still haven’t found it.)

In July 2019, I attended the third quadrennial Clemens Conference, a scholarly Twain symposium sponsored by the Twain museum. On Friday, July 26, the majority of the Twain scholars in attendance converged at Mark Twain Cave — sacred soil to all of us. We split into two groups, and I opted to join the second group with Linda. I expected we would veer off from the group to explore on our own, as we had so many times in the past.

Two fellow scholars hung back with us: Ben Click, PhD, a professor of English at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and Joe Csicsila, PhD, a professor of English language and literature at Eastern Michigan University. We told them our mission, as always, was to read as many names as possible, always in search of Clemens’. Linda waved her flashlight across the pitch-black walls and ceiling, trying to give them some idea of the challenge. There were names everywhere.

In the 1930s, electric lights had been installed along the footpath for tourists. These generate enough brightness to walk safely, but most of the wall areas remain in utter darkness. Imagine 260 passages totaling 3 miles in distance. That’s 6 miles of walls, and hundreds of agile visitors climbed high enough to write their names on the ceiling.

Looking for one particular signature was simply a labor of love. I never really expected to find this particular needle in the haystack.

As Linda flashed her light, I followed its beam trying to read the smoked, penciled and painted names. Suddenly, I yelled, “I see something! Clemens! I think I see Clemens!”

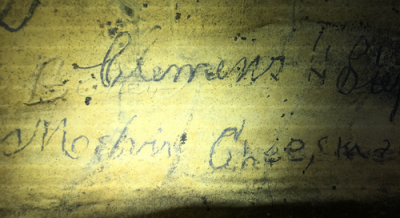

Linda returned with her flashlight as I showed her where I’d seen it. I braced myself for disappointment, assuming it would be another bust. I was stunned to see “Clemens” written in beautiful cursive. The signer had used a lead pencil.

We were dumbfounded. The four of us were rooted in that spot for several minutes while the rest of the group moved on. I took a picture, and we meandered on through the cave, showing Ben and Joe some of our favorite places while speculating about the signature. There was no first name with it, and Sam had siblings. I recall that evening as one spent in dazed excitement.

Twain scholars Alan Gribben from Auburn University and Kevin Mac Donnell, who owns the world’s largest private collection of Mark Twain autographs, confirmed the signature as Sam’s after eliminating other possibilities from examples provided by the Mark Twain Project at the University of California-Berkeley. In the meantime, I had returned and taken high-resolution photos, which clearly revealed “Sam” etched into the cave wall under the pencil signature.

Sam Clemens explored the cave as a boy on countless occasions and later immortalized the cave in his writing. The cave was named for him. It seems fitting that his signature can at last be pointed out by guides for curious tourists.

My finding the signature felt like a gift, like Sam Clemens himself whispered, “Look over there … .”

Perhaps the point of this story is to remain persistent. Or, perhaps the point is to indulge your childhood dreams and allow your imagination to consider all possibilities. Eventually, the eyes might see what you’ve only been able to imagine. Right, Sam?

-Cindy Lovell, PhD ’94, MA ’96

Cindy Lovell, PhD, earned her BA in elementary education in 1994 at Stetson and an MA in education in 1996. She founded the HATS (High Achieving Talented Students) Program at Stetson and earned tenure as a faculty member in the Department of Education, where she taught from 1999 to 2007.