Biodiversity Lecture recounts dramatic effort to save Florida panthers

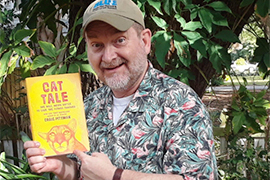

On Feb. 27, the Stetson Law community welcomed writer Craig Pittman to speak as a part of the Foreman Biodiversity lecture series. Pittman is a native Floridian and an environmental reporter for the Tampa Bay Times. He has written five award-winning books – his most recent work is titled “Cat Tale: The Wild, Weird Battle to Save the Florida Panther.”

Pittman has covered the Florida panthers for years in his capacity as a reporter, and the more he learned, the more he became fascinated by the animals. He began his talk by describing what he believed to be a statue of a panther in the State Archives in Tallahassee. It was only later that he realized the statue was a real stuffed panther and what’s more, it had a name – Florida Panther 3. Its death was a tragedy and would be the catalyst for a radical conservation effort.

But before completing that tale, Pittman explained the earliest inhabitants of the state regarded these panthers as divine beings – cats of god. In the Seminole tribe, all medicine men are members of the panther clan. Early settlers in Florida called them lions and catamounts and were deeply scared of them. In the 1800s, sportsmen came to Florida just to shoot and kill panthers. They became so rare they were only ever seen in roadside zoos. By 1958, state officials banned panther hunting, but not before the damage had already been done.

In the later part of the century, state officials focused on saving the panthers. The Florida panther was on the first endangered species list promulgated by the Endangered Species Act. Environmental activists rallied to oppose the construction of an airport in Big Cypress Swamp because it was one of the only place where panthers still lived. However, many believed the animals to be completely gone – hunted to extinction. A tracker from Texas was hired to see if he could find any surviving panthers in Florida. He found one scrawny female and signs of more, estimating there to be about 20 left.

After that, the state Game Commission designated a biologist to lead studies about the panthers, publicizing the search and raising awareness. In the 1980s, the state Education Commissioner wanted local schoolchildren to pick the official state animal, and the children overwhelmingly voted for the panther.

Pittman then explained where Florida Panther 3 fit into the story. It’s predecessor, Florida Panther 1, was the first panther to have a radio collar installed as part of an initiative to track their travels. Florida Panther 3 was fitted with a collar whose batteries began to malfunction. When the animal was recaptured to replace the batteries, a tranquilizer dart pierced its femoral artery, and the panther died. According to Pittman, this changed the public sentiment toward panthers – at least one person suggested, “just stop bothering them and let them go extinct.”

Instead, a veterinarian was assigned to tag along on some of these captures, and she began to notice oddities in the animals – genetic defects as a result of their small population. She noticed the panthers had tails kinked at a 90 degree angle, and later examinations uncovered reproductive issues and holes in their hearts.

After that, faced with the prospect of the extinction of the newly crowned state animal, state officials took more aggressive action. A captive breeding program was initiated and subsequently halted by a lawsuit filed by animal activists. The lawsuit was settled on the condition that only six kittens be captured – three male and three female. Unfortunately, all the kittens had the same genetic defects.

That’s when officials decided to try something drastic: to bring in another type of cougar to breed with the Florida panthers. That same hunter who located the remaining panther population was tasked with capturing and transporting eight female cougars from Texas to release in Florida. Meanwhile, the federal government was handing out permits to developers “the way they toss beads out at Gasparilla,” resulting in further destruction of panther habitats, Pittman said. The permits were later exposed by a whistleblower to be based on junk science.

The battle to preserve panther habitat, protect them from automobile deaths on Florida highways, and maintain continued population growth is ongoing. Pittman wrapped up his talk by sharing a bit of positive news. Thanks to the breeding program, panther populations now are estimated to be 10 times their original number of 20. It’s not nearly enough to say the animals are recovered, and they still face threats, including from the proposed toll road that would cut right through their habitats. However, the animals remain extremely adaptable, and they are constantly surprising those who study them, he said.

-Taylor Allyn

College of Law

Next Biodiversity Lecture on April 1:

The next lecture will feature Dr. Arie Trouwborst, associate professor of Environmental Law at the Tilburg University Law School in The Netherlands, speaking about, “Domestic Cats and International Wildlife Law – Turning a Blind Eye to One of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species?”

The lecture is set for April 1. This will be an online-only event and the time will be determined. To watch the lecture remotely, RSVP to [email protected] by March 31.

-Taylor Allyn

College of Law