Chris Ferguson and the Myth of Video Game Violence

Christopher Ferguson, PhD, was in grad school when a guest speaker happened to tell his class one day that “there’s no doubt whatsoever” that violent media caused violence in society.

“That was the moment,” recalled Ferguson, a Stetson University psychology professor. “I think literally it was 30 seconds of her talk. But that was what sort of triggered my interest.”

In the years since, Ferguson has become a leading researcher in the field. His studies have consistently reported no connection between real-world violence and violent video games or media violence.

On Aug. 5, when President Trump linked violent video games to the mass shootings in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, Ferguson was interviewed by scores of media outlets, including The New York Times, The Atlantic and NBC News.

“The data on bananas causing suicide is about as conclusive,” he told the New York Times. “Literally. The numbers work out about the same.”

He also wrote an article for The Conversation, pointing out that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that psychological studies “do not prove” exposure to violent video games causes minors to act aggressively.

Following that, Ferguson chaired a committee of the American Psychological Association that issued a public policy statement in 2017, calling on the media and others to avoid stating that criminal offenses were caused by violent media.

The American Psychological Association’s official policy says there is “insufficient research” on whether violent video-game use causes lethal violence. But its official policy continues to link violent video games and aggression. “The link between violent video game exposure and aggressive behavior is one of the most studied and best established,” according to the APA official policy.

Ferguson disagrees and compares that policy to the “moral panic over other forms of media” that today’s parents might remember from their own youth. A 2019 review by Ferguson and several colleagues found the APA’s policy to be flawed, seriously misrepresenting the science on aggression, he said.

“This is a field very much in transition, which can be confusing,” he said. “And the APA is a professional guild, not a science organization which can also influence the kind of things they say, which aren’t always accurate.”

Challenging the Prevailing View

Seated in his office on the third floor of Flagler Hall, Ferguson recounted how he ended up in this field of research by “accident.” He was drawn to study psychology because of his interest in criminal behavior, especially serial killers. But then, the guest speaker in the graduate criminal-justice class at the University of Central Florida made the “there’s no doubt whatsoever” statement about media violence and criminal violence.

“It was like, that’s a really kind of crazy thing to say,” he recalled thinking at the time. “That really intrigued me. If people had kept it a bit more reasonable, saying, ‘Well, we might be a little worried. Maybe it has a small impact,’ I probably wouldn’t have taken that much of an interest.

“I think that’s a character flaw of mine,” he added with a laugh. “That kind of combination of moral advocacy with some sort of statement about the science supporting that moral advocacy always gets me intrigued. Often times, the data is not as good as people would like to think that it is in support of that agenda.”

After earning a doctorate in clinical psychology from UCF in 2004, he began his own studies with college students in Wisconsin and then at his next teaching job in Laredo, Texas. At the time, studies in the field of psychology had shown a link between violent video games and aggressive behavior.

Ferguson devised his own two-year study, randomly assigning college students to play a violent video game or a non-violent video game – then testing their level of aggression by various methods. But he added a third group to his study, letting some participants chose what video game to play. If they were happier playing the game of their choice, would they show less aggression than the randomized group?

“I thought it was clever. Turned out, I got nothing at all,” he explained. “I wasn’t able to replicate any of these findings with aggression, so it didn’t matter which category they were in. None of the games seemed to cause any increased aggression.

“It was counter to the narrative at the time, which was this idea that there were consistent findings of aggression in the research literature,” he said.

He conducted another study and replicated his findings. But when he tried to publish these findings, he was rejected by research journals, he said.

His first journal article on the subject was published in 2007, a meta-analysis of video-game research that showed a tendency for “publication bias,” meaning only research that confirmed prevailing views in the field tended to be accepted for publication. In that 2007 study, he concluded: “Results of the current study raise the concern that researchers in the area of video game studies have become more concerned with ‘proving’ the presence of effects, rather than testing theory in a methodologically precise manner.”

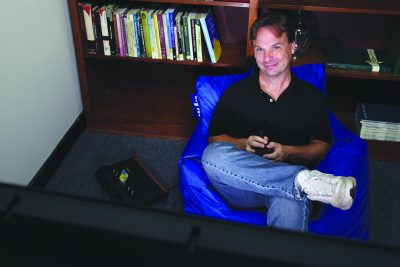

He has continued his research ever since, conducting meta-analyses of existing studies to ensure researchers used rigorous methodologies and to spot trends in their findings. He also conducts his own research, mostly with Stetson students playing video games in the Psychotechnology Lab down the hall from his office, where undergraduate research assistants collect data each academic year.

“We just finished a study on virtual reality games where we brought people into the lab and had them play different types of games and see what, if any, changes in their behavior the games cause for them,” he said. “We also do longitudinal studies where we take kids or data on kids and follow them over time and see whether playing games early in life is a risk factor for things like violence or decreased helping or things like that later on in life.”

He and other researchers, including Stetson Assistant Professor of Sociology Sven Smith, PhD, have paired up to examine data collected in the United Kingdom, for instance, to determine if playing video games or playing with toy guns predicted criminal behavior later in life – neither did.

“I spend more time writing and talking about video games than playing them, it seems like,” said Ferguson, a married father with a 15-year-old son, who like him, enjoys video games. The older Ferguson said he started playing video games as a boy on an Atari 2600 and currently plays Assassin’s Creed Odyssey on an Xbox, among others.

“A Political Decoy”

Frequently quoted in the national and local media, Ferguson said he has noticed patterns in how some politicians and media outlets react to mass shootings. The link to violent video games usually occurs only if the shooter is young, white and male.

“If the shooter is older, like the Las Vegas shooting, then nobody talks about video games, even to exonerate them,” he said. “Nobody points out that he’s a 64-year-old man and, look, clearly it’s not video games because he didn’t play any video games.”

Not long ago, both Democrats and Republicans would blame violent video games for mass killings. But these days, it has become mostly a Republican issue, he said.

“It’s a distraction from other issues like gun control or income inequality or other things that might be more productive to talk about as part of that,” he said. “I guess that’s why it’s talked about so much now is because it’s being used as a political decoy to suck up all the oxygen in the room because people’s attention span is pretty quick.

“If you can get people talking about the wrong thing for even a week, then here is it (a week later) and everybody’s forgotten about El Paso and Dayton by this point,” he continued. “It’s all a pretty good strategy, I guess. I’m sure they know what they’re doing.”

–Cory Lancaster