HONoring History

Editor’s note: This article appears in the Spring issue of Stetson University Magazine, now available online.

You never know what you might find when conducting research about history.

For example, an Orlando university student who happens to live in DeLand and work a stone’s throw from the Stetson campus uncovering the legacy of a Stetson student from a century ago.

Some explanation: Last spring, approximately 70 history students from the University of Central Florida in Orlando, working in conjunction with the National Cemetery Administration’s Veterans Legacy Program, researched and wrote biographies of veterans buried or memorialized at the Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell, Florida. Essentially, the biographies formed the basis of an online commemorative and educational resource portal designed to serve the public, using innovative pedagogy developed by a team of university professors, staff, students and K-12 educators.

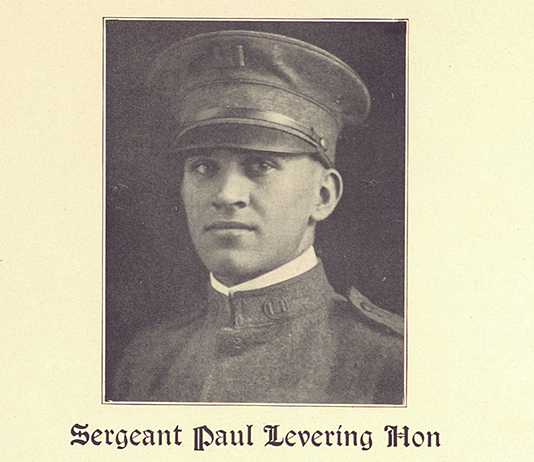

Source: Stetson University Archives

With 2018 being the centennial of the end of the United States’ involvement in World War I, UCF students were tasked with researching Floridians who served, died and were buried in France. UCF senior and history major Elizabeth Klements moved to DeLand in 2013 after high school, and works at a popular downtown DeLand eatery. So, with only a bit of initial research, Klements chose to study Paul Levering Hon, who entered Stetson as a first-year student in 1916.

“I wanted to select a veteran who was a student at Stetson when he decided to join the military,” Klements said, simply.

Then came a few surprises.

First, Klements learned the Hons were an important family in DeLand. Edmond Hon, a bookkeeper and Paul’s father, arrived in DeLand from Indiana in 1900 and worked for John B. Stetson, the university’s namesake.

With the aid of Stetson archives, Klements uncovered that Paul Hon was especially active at Stetson. He served as chair of the freshman class social committee and president of the Stetson Literary Society. He played on the baseball team, while joining the Green Room Club, a theater group, and performing a role in Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” For good measure, Hon was president of his sophomore class and a member of the Stetson Choir. Also, his brother, Howard, was a Hatter at the same time.

Klements found photos, too, by flipping through the Stetson yearbooks of 1916, 1917 and 1918. Klements recounted, with eyes widened: “When I first saw his name, I was like, ‘yes.’ Then I found his picture in a group, and I was like, ‘Which one is he? Which one is he?’ I couldn’t figure it out.”

Eventually, Klements did.

A description by business classmates in the 1917 yearbook claimed that Hon’s ambition was to “play,” while his gift was “intelligence” and his favorite pastime was “callin’ at Chaudoin Hall,” a women’s-only residence hall on campus.

As for his military story, Paul Hon enlisted as a private in the Army Engineering Corps in May 1917, a month after the United States declared war on Germany. He had just completed his sophomore year.

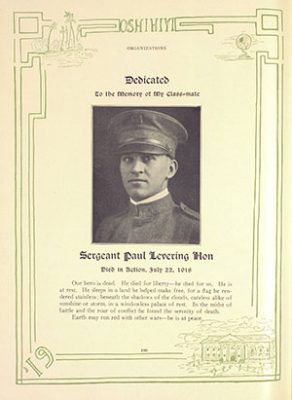

That August, his division shipped out to France, and in May 1918 Hon became a sergeant. Two months later, in July, his division engaged in the Aisne-Marne campaign. There, on July 22, around his 20th birthday, Hon died on a battlefield in Belleau, France. His remains were never recovered or identified.

In Stetson’s 1919 yearbook, a memorial page for Hon contained the following passage: “Our hero is dead. He died for liberty — he died for us. … Earth may turn red with other wars — he is at peace.”

The Hon family legacy extended long after Paul’s death. His youngest sister married into another prominent family, the Johnsons, and there was a son named Chauncey Paul Johnson, known as C. Paul Johnson. Later, he became a Stetson University benefactor. And so it went.

“The research made this sort of vague fact from World War I really personal, because you’re researching the life of someone who died in it,” Klements said, this time with sadness in her voice. “And it makes you realize that every single one of those soldiers has a story.”

Source: Stetson University Archives

“Because this work is done by college students, there’s something really profound in the experience of learning about and connecting to an American veteran who lived a hundred years ago,” affirmed Amelia Lyons, Ph.D., an associate professor and director of Graduate Programs in UCF’s Department of History.

“The stories of individual veterans help us to teach students about American history through the personal narratives of veterans. So, on some level, their service continues, because now they’re servicing K-12 students and they’re serving our students, who come away from the program with so many skill sets.”

Lyons shared her own bit of Stetson serendipity. Last summer, July 2018, Lyons was in France as an invited guest and the lone U.S. representative for a 100th-anniversary commemoration of the battle that took Hon’s life. Lyons happens to know a descendant of French Gen. Charles Mangin, who had led the Americans into that fateful, ultimately victorious battle. Lyons attended as part of the Mangin family.

The ceremony included the dedication of a reconstructed tower, one that Gen. Mangin had used as he led the assault, along with a monument to the victory in Aisne. Sgt. Paul Levering Hon is remembered on the Tablets of the Missing at the Aisne-Marne Cemetery in Belleau, not far from where he died.

“To know that Paul was out there and he’s never been recovered,” Lyons said, “that was incredibly moving.”

-Michael Candelaria