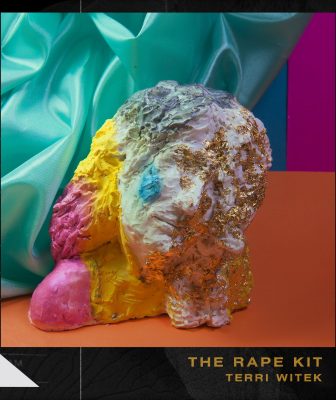

Professor Terri Witek: ‘The Rape Kit’ and Ordinary Violence

On Thursday, March 14, the Stetson Master of Fine Arts program will host a book launch for English Professor Terri Witek’s latest book, “The Rape Kit.”

Winner of the Slope Editions Prize (selected by Dawn Lundy Martin), “The Rape Kit” is a series of procedural poems about rape — how people move through it and the culture that creates such “ordinary violence.”

The Sullivan’s Writers Series Event will feature the book launch of “The Rape Kit,” with readings by MFA alumni and faculty: Lucianna Chixaro Ramos, Michelle Pavone, Teresa Carmody and Terri Witek on Thursday, March 14, from 7-9 p.m. in the Rinker Welcome Center, Lynn Presentation Room. Cultural Credit is available.

Stetson MFA-Creative Writing student Carley Fockler talked with Witek, Ph.D., English professor and Sullivan Chair in Creative writing, about crafting “The Rape Kit.” Also: collaboration, experiments, myths, traps and writing advice.

Fockler: Do you consider your work in “The Rape Kit” experimental?

Witek: I think that different things seem to call up different methods of making. For example, there’s more graphic and visual work in “The Rape Kit” than in my other books. This book has a narrative structure, and some things needed to move faster than language on the page, which moves the eyes from the top to the bottom of the page — that didn’t really work for me with “The Rape Kit.” It was too “one way” and the protagonist in “The Rape Kit” is interested in these different methods of escape or ways around the cultural language, so I did as many things as I felt I could do, even things I felt were beyond me. Lucianna Ramos, a wonderful MFA alumna in Poetry in the Expanded Field from our program, was the book designer. The fingerprint page? I turned it over to her — didn’t want to know whose fingerprints they were! Actually, I think all poetic forms and all art-making are experiments, including traditional formal verses.

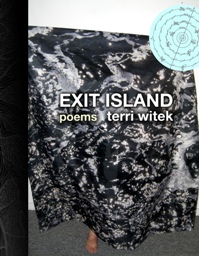

Fockler: I did notice there were more “experiments” in “The Rape Kit” than your previous works, like “Exit Island.” Was that, in part, because of the material you were writing about?

Witek: Partly. As you can see, both “Exit Island” and “The Rape Kit” have a sort of mythic female figure in them. Ariadne is really the protagonist of “Exit Island.” I was considering that Titian painting where Ariadne is mourning as Theseus sails off; Dionysus is right around the corner. The woman doesn’t even have a moment to breathe before she has to think about this new relationship. Ariadne is stolen across the water in a ship, if you remember the myth, to an island: in “Exit Island” she has to rethink “the island” and make it her own.

In “The Rape Kit,” Arethusa escapes under water. I was very interested in this myth of the fresh water nymph who is given an escape route by a goddess through the sea and manages to make her own freshwater move through salt. It’s an actual phenomenon. Up by St. Augustine, for example, there is a fresh water pocket in ocean. I was interested in this: can you escape through an element? Can you move through language? Can you move through the elements of our world and not become them? In the myth, Arethusa is pursued by Alpheus, a River God who mingles with her. In some versions it’s a rape narrative. Or the waters are conjoined and it just happens. Let’s say I’m just sort of moving my body in the body of language. I was happy that I was at last able to get off the water’s surface and move under and through it in “The Rape Kit.”

Fockler: Collaboration is very heavy in your work, both with Ramos and, of course, with Cyriaco Lopes (Witek’s long-term collaborative partner). Does collaboration create a cohesive group narrative or do you feel that “The Rape Kit” is very personal to your experiences?

Witek: I am not a comfortably autobiographical poet and I really didn’t want to write a book that would be false to the history of sexual assault because this is really one out of every four women’s story. Rape is not an exceptional narrative; it’s a story as old as gender. … The more voices included, the better. My contribution is to put the text together. Unlike things lie down together. And that’s what rape is. It’s also what any relationship is and what the book is trying to do.

Fockler: I’ve seen you read “The Rape Kit” out loud with Lopes, which was very different from when you read in Brazil, when it was just you. When I sat down and read the book, it was again very different for me. Do you have different experiences when you do these readings?

Witek: I do. The crowd really makes a difference. When I read in Cleveland, I was reading with a writer who had written a book about a social history of rape in Cleveland. He was making the argument for how things had changed – police procedures had improved, etc. That writer wasn’t a regular in the poetry world or fiction world we nominally move in and it was interesting to think about an actual city. There have been times when it was tricky for me, though. When I was going to read at University of Washington-Bothell, my daughter, Eli, and I were listening to the Kavanaugh testimony on the way to the airport. I was distraught all day and was the last reader (as a W!) that night. I really felt different in that reading— almost outside myself. So cultural circumstances and situations and audiences definitely have something to do with it.

Fockler: While reading “The Rape Kit,” I found something very cathartic in it. Is that something you envisioned while writing it?

Witek: No, no. I was just trying to avoid the traps. I didn’t want to fall into the “victim” trap and I didn’t want to fall into the “survivor” trap. When we name other people with these nominal tags, these nouns, what we’re actually doing is saying “it’s not me” and “I hope it won’t be me.” It’s a charm to fight off the darkness, to call other people names that one is not. I didn’t want to fall into that trap of being so charismatically driven that people think “oh, she’s so brave.” So there were several things I wanted to short-change. I didn’t want anyone to think about me. I didn’t want the trap of “celebrity” for rape. I’m not special: this is ordinary violence.

Fockler: You avoid being voyeuristic and you give the emotional details through the words. Was that also an important trap to avoid falling into while you were writing?

Witek: Great question, Carley, but I really don’t think about it so much now. When the second wave of feminism came, and people began to tell their stories, there was a lot of “I” poetry in women’s work. I quite loved Sharon Olds for example – this was the 80’s – and in that moment it was also clear I wasn’t going to write like that. There was something in me that resisted. I really believed that this controlling “I” is not a benevolent thing. Also, taking the “I” out just made my poetry better. I’m all about what makes the work better.

Fockler: I’ve been given the advice when writing about trauma to “push, don’t pull back.” Is that the same advice you’d give to poets or students who are writing about trauma?

Witek: I think write till you’re past it or through it or break it sounds like good advice. But I don’t think that the advice for trauma is really different from the advice for everything else. I refuse to make trauma exceptional. This is everyday tragedy. This is just us trying to muddle through. I also think that whatever advice someone gives you that works is the right advice because your duty is to your art. You can totally disagree with the advice and make it work, for example. I did that all through graduate school. I disagreed with my much-loved professors quietly, and that pushed me to have my own ideas and my own ways of going about things. Whatever advice makes you create good work and isn’t self-harmful is good advice.

Fockler: One of my favorite structures in the book is the Q&A portions and how you recreated this during the reading at our January MFA residency. Did that change what you thought about “The Rape Kit” or how you put it together as a whole, or as it exists now?

Witek: I feel compelled to put unlike things together and what is more unlike a question than an answer? Metaphor does this, too. Both are examples of how you lie two things down together. I’ve been doing Q&A cards for quite a while, you know: I did a different version of it with Matt Roberts in “Strangers, an Augmented Reality Project” at the Orlando Museum, and will do a version at the Thursday reading. I prefer things that can be both public and private simultaneously. I like that this particular Q&A involves the audience and can be very specific. So, everyone’s invited in, but we both reveal and don’t reveal; it’s anonymous and it’s also quite personal. I think that’s my M.O. in most things, actually, and it seemed particularly apt for “The Rape Kit.”