Stetson Alumna Studying Migration, Violence and Climate Change in Honduras

For Stetson alumna Rebecca Williams, the migrant caravan at the U.S. border tells a story that she has witnessed first-hand as a research scientist in Honduras.

The caravan is made up of mostly women and children, reflecting the increasing desperation at home due to gang violence, domestic violence, poverty and a corrupt government that does not protect its citizens, said Williams, Ph.D., an assistant research scientist at the University of Florida.

And Williams may soon find an even larger force behind the migration – climate change.

In January, she began a $200,000 study in Honduras for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) that will examine whether climate change is fueling the country’s escalating violence and mass migrations. Her findings will help set the agency’s policies in that country for the next five years.

The USAID study is “relevant to what we’re seeing in the news right now,” she said.

Honduras is ranked third in the world among countries most affected by climate change, she said. Extreme drought has destroyed crops, like corn and beans, which feed rural farmers and their families. And the country’s cash crop – coffee – has been plagued by a fungus, called coffee rust.

“We already have a pretty good understanding that issues of violence are connected directly to the lack of safety and the poverty,” said Williams ‘01, who earned a B.S. in Music Education from Stetson and now works for UF’s Office for Global Research Engagement.

“What we were not able to show yet, which is why we’re going back and doing a larger study, is if climate change is specifically one of the drivers as to why rural livelihoods are failing. And we suspect very strongly that is the case,” she added.

Finding her Way at Stetson

Williams first went to Honduras in 2009. At age 29, she joined the Peace Corps and became an environmental educator for two years, teaching about basic sanitation in one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere, where about 65 percent of people live below a national poverty line of $3.10 a day.

It may seem like a long way from studying music education as an undergraduate, but Williams said her career as a research scientist and Honduran expert is inextricably tied to her time at Stetson.

“I always talk very glowingly of Stetson,” she said by phone from Gainesville, just back from Nepal where she and a research team are working on another USAID project focused on six countries in Africa and Asia. “It was such an incredibly formative experience for me in so many ways.”

Williams grew up in DeLand and her father attended Stetson, as a nontraditional student who earned a music degree while she was in middle school. Ronald J. Williams ’93 was a choral student, played piano and organ, and was selected for the Presser Scholarship Award, given to the outstanding rising senior in the School of Music each year.

He also started his daughter in clarinet lessons at age 11 with Stetson Professor of Clarinet Lynn Musco, D.M. And these lessons continued until Williams was 15 and the family moved to Colorado.

“I finished high school out in Colorado, but to be honest I kind of slacked my last years of high school,” Williams recalled. “I was kind of lost and unmotivated, and the only thing I was really good at and felt confident about was music.”

At 17, she called her former music teacher and said she’d like to attend Stetson. Williams flew in for an audition, was accepted and received a partial scholarship. And, she added with a laugh, she was placed on academic probation for a year until she pulled up her grades, which she did, making the Dean’s List.

Musco said she knew her former music student could handle college course work. “From the very beginning with those lessons as a young middle school student, she was vibrant, inquisitive, smart and had a great work ethic, especially when she was challenged. … Although her record didn’t show it, I knew her. I knew what she was capable of, and so it was an easy decision to ‘take a chance’ and admit her,” Musco explained.

Williams’ undergraduate years at Stetson were shaped by close relationships — with professors, like Musco, with her roommate and with fellow members of Stetson’s Symphonic Band and Symphony Orchestra. And these relationships ultimately saved her.

“The one thing about a liberal arts school that I think is just so valuable is the relationships you have with the faculty, which you just don’t get at a big school,” Williams explained. “And I will tell you that my time at Stetson literally saved my life because my professors and my roommate and best friend, and some of my other friends noticed toward the end of my junior year that I was really, really struggling.

“My college professor intervened and helped me, and nobody at a big school like this would have noticed something like that. If it hadn’t been for my relationships there, there’s no way that I’d be where I am now and I really attribute that to the way the university is run and the size of it and the teacher-student relationships.”

Changing Careers

By her junior year at Stetson, Williams knew she was interested in environmental work, but she loved music and working with children, too. So, she graduated with a music education degree and began working as an elementary school music teacher. Along the way, she earned a master’s degree from Florida State University in Instructional Systems Design and then took a job in curriculum development at UF.

But, Williams said, “I just felt like I wasn’t making the impact that I wanted to make.” So, she volunteered for the Peace Corps, learned to speak Spanish and went to Honduras.

“Honestly, that experience is what changed everything for me. It just completely changed my perspective on where I fit in the world and what I want my life to be and what I felt like I needed to do,” she continued.

“And my experience as a woman in Honduras was really challenging, and so I decided I really wanted to focus on gender and how gender affects people’s ability to get out of poverty, especially in developing countries and so that’s what I went on to study in my Ph.D. program.”

Williams earned a doctorate from UF in Interdisciplinary Ecology with concentrations in tropical conservation, gender and development. In her dissertation, she thanked Stetson Music Professor Lynn Musco “for everything that she did for me. She wasn’t just my teacher. She was like a family and like a therapist,” Williams said. “I still so much value her and everything that she’s done for me. She’s an exceptional person.”

Those kinds of relationships at Stetson “put me on the pathway to be where I am now. … I may not have stayed in music specifically, but they put me on the track to understanding who I am and what I wanted out of life,” Williams said.

Professor Musco said she “suspected early on” that Williams might not stay in a musical field. But the skills required to become an accomplished musician are the same ones that help people succeed in other professions — things like “self-discipline, determination, critical thinking, teamwork, verbal and non-verbal communication,” Musco said.

“These four years for students at Stetson is the best time in their lives to figure out who they are and begin to pave the path to where they want to be. Sometimes all it takes is reassurance and someone believing in them to propel them to do significant things. It’s not about completing a major – it’s about beginning to define who you are and what you stand for and believe in as a person,” Musco said. “Becky personifies everything we do well here at Stetson.”

‘A Move of Desperation’

As a Peace Corps volunteer from 2009 to 2011 in Honduras and now as a research scientist, Williams has watched the increasingly desperate conditions unfold and begin to drive people from their homeland.

She is close with a family in Honduras who grows their own food. Dependent on rainfall for their crops, the family has watched once productive agricultural land turn into dry, cracked earth. In such extreme drought, their crops have failed for the past three years.

“When those crops fail, then people starve,” Williams said, adding that she has helped the family financially through the hardship. “It’s a really dire situation.”

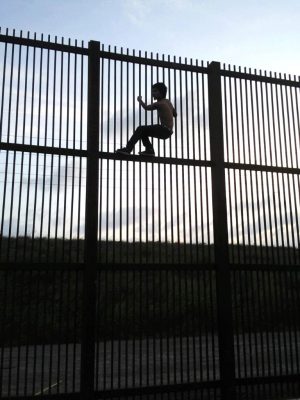

Last October, a few hundred Hondurans set out on foot for the United States, hoping to gain entry. Along the way, the migrant caravan swelled to thousands of people as it headed for Tijuana, Mexico, touching off a political firestorm that has shut down the U.S. government over funding for a border wall.

“I do want to be sure that whoever reads this article will understand that Honduras is a really a wonderful place,” Williams said. “It’s a beautiful country and it has so much potential, but right now they are really struggling. … I can promise everybody that Hondurans don’t want to leave Honduras. They love their country. This is a move of desperation.”

For her USAID study in Honduras, Williams will begin collecting data in May and expects to present her findings there this October. She also would like to raise awareness in America about climate change, social disruption, violence and migration.

“Right now, we’re so busy fighting about whether or not it’s driven by humans and who’s responsible and who’s at fault that we’re just letting people around the world suffer the consequences while we in the United States have the luxury of things like running water and air conditioning, so that we don’t notice it on a daily basis like other people do,” she explained.

Researchers have predicted catastrophic consequences for the planet unless drastic steps are taken in just over a decade to reduce the carbon emissions that cause global warming and climate change.

“Mass migration, increases in violence, especially over natural resources, First World countries putting up walls and barriers, isolating and preventing migrants from entering: all of these things have been predicted to occur with increases in climate change,” Williams said. “So, I’m trying to look at how these things are happening, and if and what we can do about it.”

-Cory Lancaster