Celebration ’67

Looking back a half-century, 1967 was one heck of a year.

The U.S. Senate confirmed Thurgood Marshall as the first African-American Supreme Court justice.

NASA launched the Lunar Orbiter 3 spacecraft for the purpose of photographing the surface of the moon.

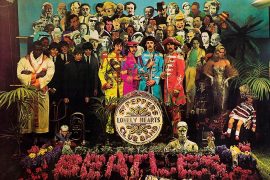

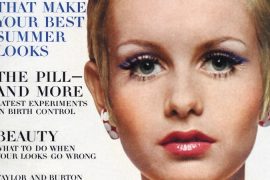

Miniskirts also skyrocketed in popularity, as the emergence of Twiggy from England sparked a new fashion sensation. The Beatles, another British import, continued to reign with the release of the all-time hit album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” And the premiere issue of Rolling Stone magazine rolled off the presses.

In Hollywood, movies appealing to younger audiences became blockbusters, including “The Graduate,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Cool Hand Luke.” The falling price of color televisions, meanwhile, ushered in a new era of home viewing.

Science fiction grew real, as James H. Bedford, M.D., became the first person to be cryonically preserved. Before dying of kidney cancer, the 73-year-old psychology professor (not at Stetson) had asked to be preserved for future revival.

Interracial marriage was declared constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Loving v. Virginia case, barring Virginia and by implication other states from making interracial marriage a crime.

Finally, the Vietnam War raged on, with a total of 475,000 American soldiers serving there and peace rallies multiplying at home. Among the protesters was Muhammad Ali, subsequently stripped of his boxing world championship for refusing to be inducted into the Army.

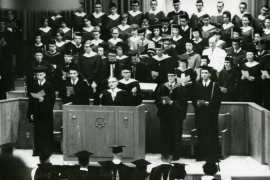

Oh, and in DeLand, Florida, on the campus of Stetson, a private liberal arts university, 232 graduates (by inexact count) were sent into a world that seemingly was changing by the minute, with a university leader, J. Ollie Edmunds, J.D., who also was departing as president after serving 19 years. The graduation ceremony was held in the Forest of Arden, just a tassel toss from campus.

The Class of 1967.

During Homecoming Week 2017, Oct. 29-Nov. 5, some of those Hatters will celebrate that past – as well as their present and future — as part of 10 class reunions taking place on campus. The others: 1972, 1977, 1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007 and 2012.

SPORT OF POPULARITY

Vining Bigelow remembers a welcoming campus, one that allowed him to play intercollegiate soccer, join a fraternity and, ultimately, serve as the business manager of the class yearbook.

Bigelow arrived at Stetson in 1963 sight unseen from Hopkins Grammar School, a New Haven, Connecticut, prep school that previously had produced Hatters. He also was joined by a Hopkins pal, John Crowther. Rather quickly, Bigelow made a name for himself.

“You get to Florida, and you don’t know who’s who,” Bigelow recalls. “And then you talk to people and find out that another one of the students had come from Bridgeport, Connecticut, about 20 minutes from where I was.

“The way I got to know people, and to be more known, was via the sports.”

There were no athletic grants at the time, whereas today the Hatters field 17 Division I teams for scholarship athletes (excluding football). Regardless, Bigelow turned himself into an all-conference player; he played on the tennis team, too.

Following graduation, Bigelow joined the Coast Guard and became an officer, thanks to a Stetson degree in business and officer candidate school. Returning home, he eventually succeeded in the business of computers – ironic considering they were in their infancy at Stetson during his time. He remembers them as basic, elementary and awkward — “and that was just to print out your name.”

Bigelow remains in Connecticut but plans to return for the reunion. In the class yearbook, he sold ads to places such as Mano’s Pizza, Kent’s Photo Shop & Studio, Belue’s Shoes and DeLand Camera Shop. They may be gone, but he hopes to rekindle an “overall great feeling about Stetson,” even after all these years.

NEW FACES

At the time, Stetson had approximately 1,500 undergraduate students, about half of the current size, predominantly white and male. The acronym “PWI” for Private White Institution assuredly was appropriate. The campus, though, was changing, gradually. The first African-American student was admitted in 1965; others followed. Ethnic diversity was showing signs of life.

Gena Medrano was part of that subtly shifting demographic palette. She would later become Gena Medrano Swartz in what emerges as an all-too-entirely Stetson story.

Medrano attended two years of high school in Miami after fleeing Cuba with her mother. An excellent student with a strong handle on English from taking language classes in Cuba, she graduated at age 16. From a counselor in Miami, she learned of a program called Away From Home, sponsored by the Episcopal Diocese of South Florida, along with Stetson and First Baptist Church. Essentially, it offered a full scholarship for the children of Cuban exiles. Medrano took complete advantage of the opportunity, joining a reported 15 others in the program at Stetson in 1963.

Self-described as wide-eyed and outspoken, she let little stand in her way, including winning the attention of her future husband, Richard Swartz ’68, who “thought I was French,” Medrano recalls. She laughs about the discrepancy in stories of how they met. She thought it was in a Saturday-morning chemistry lab during her sophomore year. Later verified by mutual friends, it turned out to be standing in line at the Commons.

“Supposedly, we were introduced,” says Medrano. “I have no recollection of that. But the rest is history.”

Medrano has kept scrapbooks about her days at Stetson, largely recollected as times of discovery and growth. As a first-year student, she learned that Rush Week was not at all related to rushing to do something. That year, she also learned about a nation’s pain through the Nov. 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy (while sitting in psychology class at Elizabeth Hall). “It was one of those things that will live in my memory forever,” she notes.

Through the years, she learned about the “generosity” of a university and its professors. “You got to know the professors, and you felt comfortable going to see a professor after hours. … They cared,” Medrano says. She was a double major in psychology and Spanish literature.

And a year after graduating, she learned about the reality of war. Like so many of the students, Medrano had befriended Max Cleland ’64, a popular Hatter and U.S. Army hero who returned from Vietnam disabled from combat.

Medrano’s experiences also are captured on a Stetson ’67 Facebook page. Mostly, they are reflected in her continual involvement with the university, where she has been an especially active participant in the planning of the class reunion.

“I love Stetson,” she concludes, simply. “I just love it.”

MORE ROMANCE IN THE AIR

John Crowther and Margaret Smith also remember America’s fateful November day in 1963, long before they became the Crowthers.

Each arrived on campus as a first-year student in 1963, with John coming from Hopkins Grammar School in New Haven, Connecticut (as did Vining Bigelow), and Margaret from nearby New Smyrna Beach High School. They were likely among the first on campus to hear the President’s news, as the two were in the television room of Chaudoin Hall, following lunch in the Commons and waiting to go to their classes. Both agree it was the most vivid memory of their years at Stetson.

There were, however, plenty of happy times. John worked in the post office and in a bowling alley located above the bookstore, and participated in fraternity intramurals (football and basketball). Sigma Phi Epsilon won the President’s Cup in 1965, he proudly reveals. He also was a member of Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society and active in the ROTC program, where he was a member of the Pershing Rifles and Scabbard and Blade military fraternities. He was awarded the Academic Achievement Wreath and designated as a Distinguished Military Student. He received a master’s degree in social studies in 1969. He graduated from Stetson University College of Law in 1974, following overseas service in Korea – making it three degrees from Stetson.

Margaret was a member of Alpha Xi Delta, as well as the Stetson Concert Band and Beta Gamma Sigma (business honorary society). Under a work grant, she served as a professorial secretary in an old white building where the Hollis Center’s swimming pool now sits. Following graduation, while John remained on campus, she began teaching in nearby Sanford.

They had become first-year sweethearts. John says he spotted Margaret in a biology class on the first day of school, but they didn’t meet until a lab class two days later. John tells the story: “After lab class, I asked her if she’d like to go to the Greek Week Dance at the old Riviera Hotel in Daytona Beach. She said, yes, and we both went off to our respective dorms [Smith Hall and Chaudoin Hall] after agreeing to meet for dinner in the Commons. When we got to the dorms, we both realized that we hadn’t agreed to go to the dance with each other; we had only said that we’d both like to go. We straightened that out over dinner, went to the dance [double-dating with my fraternity brother and his date], and we’ve been together ever since.”

They were engaged before classes began in fall 1964 and married a year later, during their junior years.

Essentially, the couple represented the fabric of Stetson’s student body at the time, and still today: actively engaged, eager learners and very busy young people who were focused on their success.

“Students seemed to be generally more oriented toward their life on campus than with the goings-on off campus,” describes John of the mid-1960s, pointing to Stetson’s affiliation with the Southern Baptist Convention and the required chapel services and courses in Christianity and Western Thought. “The campus was its own little community within the DeLand community.

“Students were conservative in both their hairstyles and dress, with men wearing slacks and button-down shirts to class, and women wearing dresses, skirts and blouses. Flip-flops, T-shirts and Bermuda shorts were not worn to class. It wasn’t until about 1969 that the campus began to change and experienced what I would describe as some ‘counterculture’ episodes, such as anti-war rhetoric and small groups of demonstrators.”

Living in Orange City near DeLand, the Crowthers have remained involved with their alma mater. So, of course, the reunion is an absolute — planning their return to Florida from their mountain retreat in Tennessee just in time to be there. And, in the end, there are 13 earned degrees from Stetson in the Crowther family over the span of five generations, including their daughter, son and grandson.

Another love story (a recurring theme): Elizabeth Walker and Jay Mechling both grew up in South Florida. They didn’t know each other at first. They also needed lots of help to get to Stetson, with their ability to attend heavily dependent on the financial aid the university provided.

Yet, less than four years later, they were married, living in an apartment above a garage on the edge of campus that was used by a group of students as the site for an “experimental theater.” The apartment was furnished with abandoned furniture left in a burned-out Sigma Nu fraternity house and discarded patio furniture from the Hat Rack dining area.

The two had met as first-year students, began dating as sophomores, got engaged as juniors, and then were wed before graduation.

“The original plan was to get married in June back in Miami Beach, but we realized that we wanted to get married where our friends were,” says Jay, who majored in American studies. “So, we got married in March of our senior year at Stetson during Easter/Spring Break.”

Such were the times for Hatters (and still remain today): Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Their romance blossomed that sophomore year. Elizabeth, a double major in English and speech/drama, had a work-study job in the speech office, while Jay had one in the American studies office. By chance, those two departments shared an office suite on the second floor of Sampson Hall. Neither Jay nor Elizabeth had a car, so “dates” usually meant long walks downtown, window-shopping. They also took long walks through DeLand neighborhoods surrounding the campus.

“On those walks,” says Jay, “we fantasized that someday we would be able to live in a house as grand as those we saw in the neighborhoods. We also made out on those walks.”

Other fond memories revolved around teachers and, like for so many students, they happened amid a backdrop of mostly racial segregation, Vietnam and the fear of being “outed” for sexual preference. “Social mores were changing in the 1960s,” comments Jay, “but being gay at Stetson in those years must have been a very painful experience.”

The couple then departed for grad school, leaving Stetson with a roadmap to success along with the memories.

“At 18, Elizabeth thought she could not go to college and could not have even applied to Stetson without the loan of an application fee from her high school counselor,” says Jay. “She earned her B.A. at Stetson, her M.A. and Ph.D. at Temple [University], was a professor at two California State University campuses and dean of the School of Communication at Cal State University – Fullerton. Thanks to Stetson.”

Two years ago, Jay returned to campus as part of alumni leadership that made the Stetson University Vietnam Remembrance Site a reality on campus.

PLAYING BY THE RULES (SORT OF)

Although events of the day were occasionally evident on campus, Ron Hall remembers a Walter Cronkite moment on the national TV news. Cronkite, the generation’s preeminent newsman, cut to video, not of another protest by college students, but an “orange fight.” While people are throwing snowballs up North, said Cronkite, students at Stetson down South were throwing hard green oranges in playful fun.

“This was a mainline pop-culture place,” says Hall, who now goes by Ronald L. Hall, Ph.D., Stetson professor of philosophy.

Looking back, Hall’s time as a Hatter could be considered offbeat, maybe even a bit rebellious, although in a kind of cordial way. Coming from high school in Sarasota, Florida, he was a philosophy major from day one and an independent thinker. Similarly, while Greek life was big on campus, he didn’t follow the trend. “Everything [for me] was divided between philosophy and romance,” he says.

The romance (that theme again) came in the form of (another) Margaret Smith, a student at the time, whom he met at the Commons (quite apparently a haven for romance). It was Hall’s sophomore year. She was sitting with her roommate; he was doing the same with his roommate. The young ladies joined Hall at his table. “I was stunned. They got up and left, and I told my friend, ‘I’m going to marry her,’” Hall says.

By the end of that year, they were married, and they later moved into an on-campus apartment.

Hall also became acting assistant dean of men while still a student. He had been the head resident on campus with a staff of resident assistants before advancing to that role. He owned a 1967 Mustang, too, another cause of attention and, as he says with a laugh, even some disdain.

Hall, however, adds he always maintained great respect for his professors (fitting since he is one now) and was a Hatter through and through, which meant something special.

“There was a camaraderie here that was friendly,” he offers. “This

was a very nice place to be.”

Anita Williams (now Cohen) doesn’t disagree, but she does provide a varying perspective. A member of the Alpha Xi Delta sorority, she enjoyed having fun. Her favorite pastimes were Alpha Xi parties; intramural sports, as among the first female participants; hanging out in the Hat Rack; and driving to the beach in her “VW bug” with friends, each of whom chipped in a quarter for gas.

There was a downside.

“On campus, the rules were strict and seemed as if they were made to be broken,” says Cohen, who had arrived from St. Petersburg, Florida. “My friends and I had various minor infractions, but most of us survived to graduate.”

Cohen remembers great escapes, or actually great entries: “I have vivid memories of friends climbing in and out of my first-floor window in Emily Hall to avoid the guardians of the front door, when curfews were so unreasonable! Of course, I never did that.”

There was a curfew for women, not for men.

“How is that fair? It was really hard to get back by 10 [at night], I can tell you,” she continues. “Especially when we knew the guys were going to stay out partying! They [administrators] kept track of our ‘late minutes.’ Once you reached a certain number, you had to go before a council of your peers and get disciplined.”

She majored in math, where she excelled until taking advanced calculus, which “I never understood.” And she was bitten by the Stetson love bug (of course), marrying another Hatter.

“My fondest memory,” she says, “was my first date with my future husband [Rich Cohen ’66], with whom I just celebrated 50 years of marriage. We went to Daytona.” They met when she was a junior, a couple of months before his graduation.

Cohen now lives in Las Vegas and only wishes she could make it back to campus in November. Her words, with a hint of melancholy: “I would like to be beamed there.”

– Visit Stetson University Homecoming 2017 to register and for a complete schedule of events from Oct. 29-Nov. 5. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram @StetsonHomecoming.

– Michael Candelaria

Note: This article appears in the Fall 2017 issue of Stetson University Magazine.