This Week’s Sacred Space: Learning About Compassion

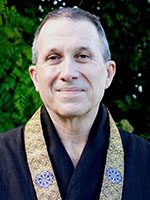

By Sensei Morris Sekiyo Sullivan, Stetson University Chaplain

On Tuesdays, I go to prison. Specifically, I spend the afternoon in the chapel at a state correctional institution, meeting with a group of inmates who want to meditate and live a more spiritual life.

In my particular tradition, we talk a lot about compassion. This is not unique to us, of course. Every major religion, at least, recognizes the value of compassion to individual spiritual wellbeing and to the health of society.

There is an inmate in our group, I will call him Franklin (not his real name). Franklin is about 10 years into a 30-year sentence for drug dealing and related charges. He’s kind of a difficult guy — opinionated, argumentative and sometimes arrogant. One day, as our meeting ended, another inmate sidled up to me, motioned toward Franklin, and asked me, “Do I really have to have compassion for that guy?”

That’s a good question.

Having compassion for difficult people is hard — it is much easier to have compassion just for people we like. Then we can have compassion for the victims of crime but not for criminals. We can have compassion for kids who get bullied but not for bullies. And so on. What could possibly be wrong with that?

I looked at the inmate who was asking me the question. He was clearly angry, and his anger was understandable. So, I said, “No, you don’t have to have compassion for him. You don’t have to do anything. But do you want peace of mind?”

Compassion is the solvent that dissolves anger’s hold on our consciousness, so to practice compassion is to move closer to spiritual freedom. This isn’t as easy as just “not getting mad.” Compassion requires understanding. As the inmate and I talked, he recognized Franklin’s annoying behavior is actually the form his suffering takes.

Compassion is the desire for someone to not suffer. It arises naturally when a friend has a personal crisis or when we hear about people harmed in a big crisis. We can develop a greater capacity for compassion by learning to recognize suffering when we see it in others, even when it manifests in actions that annoy us or cause us problems. When we learn to do that, we also begin to understand our own suffering better.

This doesn’t mean we make excuses for people, put up with harmful behavior, or go around feeling warm and fuzzy toward everyone. When you have the chance to have compassion for a difficult person in your life, try not to cause any harm. Avoid physically harming them, of course, but also avoid acting out of ill will.

Most of all, avoid harming to your own mind by letting hateful thoughts take root and grow.

CALL TO ACTION

In the coming week, if you want to try becoming a more compassionate person, be a little more generous toward someone you can help. That doesn’t mean you have to write a check to a charity. You can be generous with your time or your attention. So, give something to someone. If you want to make it even better, be generous to someone when you find it especially difficult.

Note: Stetson University’s three Chaplains share an interfaith message during Sacred Space, a weekly gathering on Mondays at 7:15 p.m. at Lee Chapel in Elizabeth Hall. They also write this column for Stetson Today that ties into the theme of this week’s gathering. For more information, contact the Office of the Chaplains at [email protected] or 386-822-7523.