Capturing a Moment: An American’s Gaze on a Late Empire

“Tradition and Innovation in Russian Art,” an exhibition at Stetson University’s Hand Art Center, features “some incredibly beautiful pieces,” said center director Tonya Curran.

Those works include 18th-century egg tempera paintings of “God the Father and Son” and “Virgin Mary and Jesus,” and a pair of elephant-shaped bookends crafted by Peter Carl Faberge from chalcedony quartz.

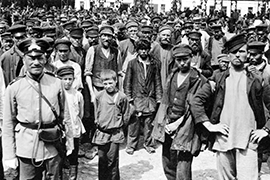

But those works are being trumped by the exhibit’s sepia-toned photos of Russian peasants, orphans, glowering Rasputin-looking priests, stiff-backed police, champion race horses and the occasional aristocrat taken by an American wandering around pre-revolution Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Visitors, Curran said, have been “really drawn” to those 38 photos that were taken in 1909 by American harness racing journalist Murray Howe, who was invited by horse racing magnate C.K.G. Billings to accompany him on a tour of Russia.

“My great-grandfather was over there taking pictures of race horses as a guest of the tsar,” said Andrew Murray Howe V, who presented the lecture “Empire and Empathy: Russian Photographs by Murray Howe” on Thursday, Sept. 28, at the Hand Art Center. The exhibit runs through Oct. 14.

His great-grandfather “was paid to document the horses that were being exhibited (by Billings),” added Howe, a real estate developer who lives in Atlantic Beach. “He was not paid to do what these pictures are all about.”

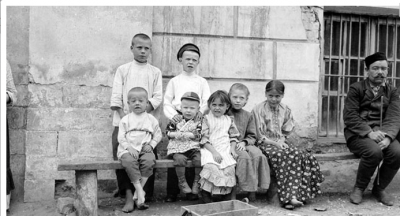

The “empathy” part of the title of his lecture comes from the gregarious, fraternal nature of his great-grandfather, who was “what today you’d call a Renaissance man,” Howe said. “He was 6-foot-3 in a time when everybody else was 5-foot-7. He was an attention-getting guy who people were drawn too. He liked kids. He liked people. He liked poor people. He liked peasants. He was just that kind of guy.”

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was still eight years away when the elder Howe was roaming the streets of Moscow with an American interpreter and a Graflex camera, an expensive and innovative piece of equipment that allowed Howe to take photographs without using a tripod.

“He was actually photographing the upheaval in the streets that was causing the conditions for the revolution, without realizing that was what he was photographing,” Howe said.

Still, there were signs: His photography activities led him to be arrested by wary police 28 times during his six-month stay, but his bonhomie led to his quick release each time. He also aided his cause by flattering judges by taking their picture “without waste of film,” the elder Howe wrote. That is, Andrew Howe told the packed seminar room at the Hand center, his great-grandfather had no film in his camera at those times.

Howe cautioned his audience that there is more to his great-grandfather’s Russian sojourn than is revealed in the exhibit’s 38 photographs. After all, the elder Howe’s Russian collection includes some 400 photos.

The exhibit includes “a very poignant photograph of a Moscow orphanage, and you see these kids who look like they’re about to cry,” Howe said. “It’s almost tear-jerking. Well, I have another photograph where they’re all laughing. There are multiple photographs where kids are following him around and making faces.”

One of Murray Howe’s most famous photos is a shot of Moscow’s Thieves Market. The photographer himself annotated the photo by writing: “I was mobbed by this crowd after taking this picture and had to be rescued by the Soldier-Police.”

“I think ‘swarmed’ is a better word,” Andrew Howe said, noting his grandfather liked spinning a yarn. In this instance the photographer was attracting an ever-growing crowd of people who were curious rather than threatening.

“I think it was a just the unusualness of someone with a camera, and a big-ass American with a camera at that,” Andrew Howe said.

Mayhill Fowler, Stetson Assistant Professor of History and Director of Russian, Eastern European and Eurasian Studies, attended the lecture and said Howe’s photos are historically significant “for a couple of reasons. One — they really show an American’s point of view, that American gaze on the late empire. They capture that moment. A Russian photographer would have seen something totally different.

“And he was experiencing life at all levels. He’s walking around the Thieves Market with his interpreter, but he’s also being treated by the creme de la creme of aristocracy in this world of trotters and horse racing. He’s really getting a slice of life, and that foreigner’s gaze. That’s quite rare.”

Howe’s photos have been a boon for her classes, Fowler said: “We’ve used this exhibit in all of my classes. The students have really loved working with these photos. It’s a treasure trove for them.”

Along with the photos’ historical value, Curran believes they “have an aesthetic quality that takes them past the merely documentary. There is a sort of sophistication about them and how he managed to frame his subjects that definitely goes beyond the documentary component.”

If You Go

“Tradition and Innovation in Russian Art” is on display through Oct. 14 at the Hand Art Center, on the Stetson campus at 139 E. Michigan Ave., DeLand. Admission is free and open to the public.

Except for holidays and university breaks, the Hand Art Center is open 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday through Wednesday and Friday, 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Thursday and noon-4 p.m. Saturday.

— Rick de Yampert