Final Act

This article appears in the new Summer Issue of Stetson University Magazine. To read the entire magazine, click here.

It’s been 23 years since Stetson held its first show of works by Oscar Bluemner, and an even 20 years since Vera Bluemner Kouba, his daughter, left her vast collection of his works to the university and began the process that led to the opening of the Hand Art Center on Stetson’s historic campus in DeLand, Florida, in 2009.

Along the way, Roberta Smith Favis, Ph.D., has cataloged the collection, sifting through the more than 1,000 sketches, paintings, notes and archival materials that form the art center’s core. The former chair of Stetson’s art department drew on that experience to write “Oscar Bluemner: A Daughter’s Legacy” for a 2004 exhibit. Favis also has published her research on Bluemner’s life and work widely, plus presented papers at the College Art Association and other scholarly conferences, and contributed essays to other institutions’ catalogs for Bluemner exhibits.

So, you might think that now, as she reviews the fragile works in the secure inner chamber at the heart of the art center’s storage area, selecting the pieces for the exhibit set to open this fall, Favis would work quickly. After all, “Oscar Bluemner: Vision and Revision: Works from the Vera Bluemner Kouba Collection” (Aug. 18-Dec. 8) is the 24th display she has organized for Stetson.

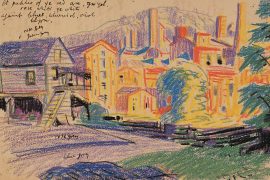

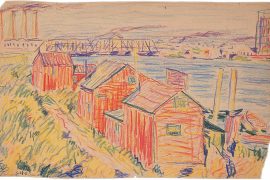

But, no. Favis gently opens a shallow metal drawer to find the small watercolors and sketches on the list that she consults and confirms with her student assistant, Abbey Ramsbottom ’18. Then Favis unfolds an archival glassine packet to reveal a postcard-sized black-and-white landscape and its minuscule notations.

“‘The red barns stand quite out of plumb’,” Favis says, quoting Bluemner’s jottings.

“He’s talking to us,” adds Favis, still delighted after all these years by the artist and his meticulous system. “Look at the values in this charcoal sketch! They’re almost like colors! And this one — ‘at evening, west, with locomotive smoke blue-black and white.’”

The curator turns the stacks of archival boxes resting on tall metal shelves in the quiet, cool room.

“Where do we want to go now? Let’s go for Box C,” she continues. “I depend a certain amount on serendipity — you’re always finding things. Bluemner said about John Marin [early American Modernist artist] that he ‘floats his colors on while I hammer mine on.’ You can see it here, and in these other works.”

Favis looks around the spacious storage room. To one side, racks of paintings stand ready to be slid open, near shelves for three-dimensional pieces; one wall holds metal drawers for the works on paper, and the metal shelving is on another. It’s a spare workplace, but one with the state-of-the-art equipment that works on paper demand. There are the usual temperature and humidity controls, but also a sophisticated fire-suppression system — no sprinklers here.

“When we first saw them, they were in envelopes under a sofa, in Vera’s DeLand house,” Favis says about the art.

A NEW HOME

The 23-year-leap from that first exhibit, taken from the home where Bluemner’s daughter had moved with her late husband, to Favis’ latest effort — her final one as she steps down after 17 years as curator of the Vera Bluemner Kouba Collection — is the stuff of legend. Works she had kept in her house now are permanently protected in the art center, itself a structure that grew out of Kouba’s gift to Stetson.

Even now, Gary Bolding, M.F.A., is impressed with the change. The Stetson art professor was the first to visit Kouba, then in her 90s, in the summer of 1994. He got a call from the university’s development office, saying the artist’s daughter liked Stetson. She had wanted to be a concert pianist; after she and her husband came to DeLand, they enjoyed concerts on campus.

“I knew a little about Bluemner, so I went to her house in a suit — and she didn’t have air conditioning,” Bolding recalls. “The University of Minnesota and a private dealer were talking to her. They were swimming around her like sharks, but she liked us. The works were so neat! It was pretty amazing.

“There were the folios under the sofa, in chests of drawers, there were Japanese prints he collected, Cezanne books with his annotations, even a Kaiser’s medal from when Bluemner was an architecture student in Germany. It isn’t really a surprise that Mrs. Kouba’s gift led to the creation of the art center. It is more of a relief.”

“Roberta became the hub of the wheel, for sure,” Bolding continues. “We told Mrs. Kouba that if she left the works to Stetson, they wouldn’t end up in a basement; we’d be sure they got a good home, and we have fulfilled our promise. The gift was also an incredible opportunity for Roberta as a scholar, to have this research material, and she’s become a renowned expert on Bluemner.”

Serendipity played a large part there, too.

The art historian earned her degrees from Bryn Mawr (B.A.) and the University of Pennsylvania (M.A., Ph.D.) — with Favis delivering her thesis just before delivering her second child.

After she and husband Greg, a doctor, moved in 1979 to his hometown in the Daytona Beach area with their three children, Favis became curator at the Ormond Memorial Art Museum and taught at Daytona Beach Community College (now Daytona State College) and Stetson. She was part time at Stetson, then full time from 1989 until she retired, becoming professor emerita in 2011.

‘REALLY LUCKY’

At Stetson, she taught classes ranging from the Survey of Western Art to Issues in Contemporary Art and Seminar in French Impressionism. She presented her work at conferences, appeared on panels, and wrote catalog essays and scholarly articles on topics ranging from Medieval, Renaissance and Modern art to 19th-century artists who worked in Florida, among them Worthington Whittredge, Thomas Moran and Martin Johnson Heade.

“I was really lucky,” Favis says. “At one point, I was interested in Moran, who came to Florida on an assignment for Harper’s or another illustrated magazine. Heade was another serendipitous topic that fell into place. And then there is Bluemner! I was in North Carolina on a National Endowment for the Humanities program when Gary called me about Vera. He was blown away by what he saw.

“We went to work, and while Vera was still alive, we gave her a little show of her father’s works, in the cases outside the old gallery in Sampson Hall [on campus]. She was in a wheelchair, and when President Doug Lee spoke, she was in tears.”

In 1997, Kouba died. Her estate was settled in 2000, and the work of appraising and cataloging the work began.

Favis called the process “stair-step,” and the timing brought more good fortune.

“We had been trying to get a climate-controlled space with a small exhibit area on campus,” she explains, “and Homer and Dolly Hand had been looking for a place to endow.”

The pace picked up when the federal Collections Assessment Program grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services recommended a professional facility. It opened as the Hand Art Center.

Stepping away from Stetson won’t be easy. Favis does have plans, however.

“Of course, I’ll miss the interaction with the students and the way I could jump around in various areas of the humanities, and I’ll miss working on the exhibits,” Favis says. “But there are other things I want to do and be. I’m a certified Florida Master Naturalist, and I’m looking forward to my 50th wedding anniversary next year, when we’re thinking of taking the whole family to Ireland.”

-Laura Stewart