Finding His Way Out

Alex Greene was 15, waiting for a city bus to take him from an Atlanta inner-city housing project to a better school across town, when a carjacking happened right in front of him.

It was a freezing winter morning, about 7 a.m., and Greene faced two bus rides and a train ride to attend a better high school out of his zone. He stood alone, as he usually did, making sure he didn’t get caught up in any trouble.

“This guy was standing in the middle of the street talking about, ‘I just got jacked. They stole my car.’ And I thought he was crazy,” he recalled. “Out of nowhere, this car comes zipping down the street and he’s like, ‘That’s my car.’ He’s in the middle of the street, telling them to stop, so the guy swerves out the way, jumps the curb and almost hits everybody on the sidewalk. And I was just like, I’ve got to get out of here.”

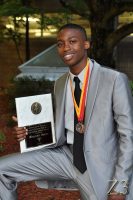

Greene found a doorway out of his crime-ridden neighborhood and has an inspiring story to tell about overcoming adversity and poverty. He graduated number two in his high school class, earned a Bill Gates Millennium Scholarship and graduated from Stetson University in December – the first in his family — with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. He hopes to attend graduate school and work for the FBI.

“I love Stetson. I don’t think I would have survived anywhere else,” said Greene, 23, who credits the small classes and close relationships with professors.

According to one longitudinal study by the U.S. Department of Education, just 12.6 percent of African-Americans of low socioeconomic status earn a bachelor’s degree or higher. Poor whites do only slightly better, with 14.4 percent earning a bachelor’s degree or higher. As income rises, so does college attainment in all racial groups, reaching 42.5 percent for blacks of high socioeconomic status and 63.2 percent for affluent whites.

The disparity in those statistics has fueled a movement for social justice in education that Greene’s mentor, Stetson Associate Professor of Education Rajni Shankar-Brown, Ph.D., has made her life’s work. To her, the numbers tell a story about the obstacles faced by students in poverty, especially students of color living in poverty.

“In getting to know Alex, I quickly learned that there were instrumental people in his life – such as his grandmother and a teacher who cared and believed in him, and with those few people who were able to say, ‘We believe in you. We’re not going to give up on you,’ he developed resilience and pushed through challenges. He came to Stetson, he became a student leader on campus, and now here he is graduating.”

“God Heard and Answered Our Prayer”

Greene was born to a single mother in Atlanta’s inner city who worked as a hotel maid and already had twin daughters, three years older than him. They shared a bedroom in his grandmother’s house. Only sporadically did he see his father, a high school dropout who worked various jobs.

When he was in second grade, his mother moved out of his grandmother’s house and into a housing project with her children across town. It was a crime-ridden neighborhood where drug use and alcoholism flourished, he said. He missed 67 days of school that year from sickness, which now he attributes to poor nutrition. Sometimes, he might find ramen noodles, Capt. Crunch cereal and milk in the kitchen; other times, only ketchup.

“Some nights I had to go to bed hungry,” he said.

He didn’t want to attend schools near the projects, so he used his grandmother’s address to enroll in middle and high school back on the east side. But he had to get there on his own, and some days he missed school because he didn’t have the bus fare and train fare.

When his grandmother found out, she started buying him tokens. A bus driver for Atlanta’s public transit agency, she knew her grandson — who liked to read and earned straight A’s — was very smart.

“I was always telling Alex, ‘You’re going to be something in life,’ ” recalled his grandmother, Jacqueline Gant, now retired.

Added Greene, “My grandmother is the primary force of my success.”

By middle school, Greene was spending weekends with her. During the week, after school and basketball practice, he’d visit her, his aunt, godparents or friends – just to avoid going home. Usually they’d feed him, never realizing he might go hungry otherwise.

His “nomad” existence continued until the summer before his senior year. He had an argument with his mother and she sent him to live with his father. He left there after a few tumultuous months, vowing to be homeless before he’d go back. That’s when his grandmother suggested he move in with her.

“If she hadn’t taken me in, I would have been somewhere totally different and I probably wouldn’t be here right now,” he said in December, right before graduating.

Throughout his childhood, teachers had noticed his academic ability and taken an interest in him. That continued at Maynard Jackson High School, where a teacher and another educator steered him toward college.

Lola Azuana, then director of the College Bound Center, said Greene had an “intrinsic desire to be better” and talked about “not wanting to be a statistic” in a city where only 38 percent of African-American boys graduate from high school.

He entered his senior year with the third-highest grade point average in his class. His homeroom teacher, Erica Hall, encouraged him to apply for a Gates Millennium Scholarship, which provided tuition, room and board for 20,000 students from low-income backgrounds to attend the college of their choice.

The envelope arrived in the mail on April 19, 2012. “When he opened that big envelope, he looked at me and fell to his knees and started to cry,” his grandmother remembered. “I was crying and he was crying. This boy is going to college for free. How many black kids get that?

“When we filled out the application, I started to pray. I said, ‘God, you know I don’t have any money to send this kid to school.’ God heard and answered our prayer.”

The Challenge Ahead

After his high school graduation, Greene received his report card and realized he’d moved up a notch to salutatorian of his class. His GPA: 3.97. He was accepted at a half dozen colleges and chose Stetson, a college that would “help him get somewhere in life,” as one of his mentors in high school said.

He wasn’t the first in his family to attend college – his uncle attended college in Tennessee on a football scholarship and his twin sisters attended college in Georgia. But all three left before graduating.

That illustrates the challenges faced by many first-generation college students.

“Some come from high-poverty public schools that may struggle with a number of serious challenges such as teacher retention, finding qualified teachers, teachers working under high stress, and lack of resources,” said Stetson’s Shankar-Brown. “That learning environment can’t compare with more affluent public and private schools. Suddenly, the inequities of K-12 schools arrive on campus.”

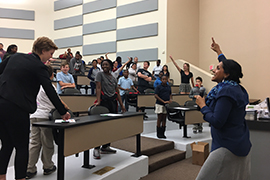

Recognizing these challenges, Stetson administrators have created a number of programs to help first-gen students. These students can receive tutoring, a student success coach, peer mentor, extra academic advising, guidance on financial aid, and help joining campus organizations, where they can connect with other students and make friends. These are services that all students may need during college and, when paired with support from family and professors, and their own resiliency, can help them reach graduation.

“We have numerous first-generation college students here, which I value. They make up 30 percent of Stetson students. There are many obstacles they face every day,” Shankar-Brown said. “In terms of equity issues, the fight does not stop at K-12, but it continues.”

The challenges are a national issue, said Kelvin Harris, Director of Leadership Development Programs for the Gates Millennium Scholars program. Gates scholars were selected based on academic achievement, but many reported struggling when they arrived at college.

The scholars cited a lack of classroom confidence, challenges forming close relationships with other students, and being shocked at the rigors of college academics, he said. Unfamiliar with college culture, they were unsure of the resources available or how to locate them.

“This concern points to the national issue of college readiness affecting first-generation students, who are largely students from low socioeconomic backgrounds and students of color,” Harris wrote. “The conversation of college readiness for this population of students suggests a larger issue of social economic disparities related to educational attainment.”

Added Shankar-Brown, “On one hand, we have this great notion that education is the golden key. It is the vehicle to freedom and justice, but in our society unfortunately many times education is part of the problem. Our institutions and systems, the way they are built and operate, often perpetuate these very inequities that we say education is built to break or eradicate.”

Giving Back

Greene experienced some of these challenges when he arrived at Stetson in 2012. For example, he enrolled in calculus his first semester. He was a math whiz but hadn’t taken calculus in high school because it wasn’t offered. Quickly, he became lost in class.

“When I first got to Stetson, it was the biggest culture shock,” he said. “I was salutatorian. I was smart, but coming here, I did not feel like that at all at first. … The schools we went to didn’t prepare us for college.”

In high school, he made straight A’s without studying. At Stetson, he was overwhelmed by the amount of information coming at him.

“Freshman year, I needed study habits and I never learned study habits,” said Greene, who later volunteered as a SU First peer mentor to help other students like him. “I wanted to quit a thousand times over. But I had a lot of encouragement from my grandmother and my family. And then I finally figured it out and got myself back on track about sophomore year.”

He also found encouragement from professors, including Rajni Shankar-Brown and Gregory Sapp, Ph.D., a Stetson Associate Professor of Religious Studies.

“A lot of us take for granted what we get, but he isn’t one of them,” Sapp said. “He was grateful for everything he had at Stetson and he made the most of it.”

Greene will return to Stetson in May for Commencement, with a “caravan” of proud family members. Until then, he’s living with his grandmother in Atlanta. The Gates scholarship will pay for grad school, but only in seven fields, such as computer science and education. He wants to study criminal justice and work for the FBI, and is figuring out how he might pay for grad school. He’s also helping at an inner-city ministry.

“I want to give back to kids in my position,” he said, “and show them, hey, you can do this. You can make it out.”

-Cory Lancaster