Free Speech vs. Free Elections

by George Salis

Financing political campaigns has always been a hotly debated issue, even more so in recent years due to steps taken to deconstruct past reforms. On one side of the argument are those concerned about the freedom of speech that reform might hinder. On the other side are those concerned about the power of the wealthy who, under slack or nonexistent laws, might squelch the voice and influence of ordinary citizens. Both concerns are worthy of a closer look.

Late in 2014, a bit of legislation regarding campaign finance reform was passed that was hidden within a voluminous, 16,003-page, $1.1 trillion spending bill intended to prevent a government shutdown. As CNN reported: “One provision will allow for increased political donations, specifically the amount donors can give to national parties to help fund conventions, building funds and legal proceedings, such as recounts.” Because of this new provision, donors could now give $32,400 (the previous cap), plus $97,200 for each of those three items – for a total of $324,000 annually.

The United States Supreme Court also is fueling deregulation. In its 2010 decision on Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, the court ruled that corporations have a constitutional right – namely, freedom of speech – to spend as much money as they please on political ads in candidate elections.

“In this case it seems the court is coming down on the side of the right of individuals to hear all sorts of different messages about campaigns – including from corporate sources,” said Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, J.D., assistant professor of law at Stetson University College of Law. “But I think it’s a real concern that the court, in its deregulatory approach to finance, is giving more power to the already powerful.”

“In this case it seems the court is coming down on the side of the right of individuals to hear all sorts of different messages about campaigns – including from corporate sources,” said Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, J.D., assistant professor of law at Stetson University College of Law. “But I think it’s a real concern that the court, in its deregulatory approach to finance, is giving more power to the already powerful.”

The decision falls out of line with a 1976 decision in Buckley v. Valeo, which held — in the wake of the Watergate scandal — that spending restrictions on an individual is not a violation of free speech but, rather, increases the “integrity of our system of representative democracy,” which is potentially undermined by unlimited contributions. Buckley simultaneously decided that restrictions on personal or family resources of a candidate were indeed a violation of free speech.

Consequences

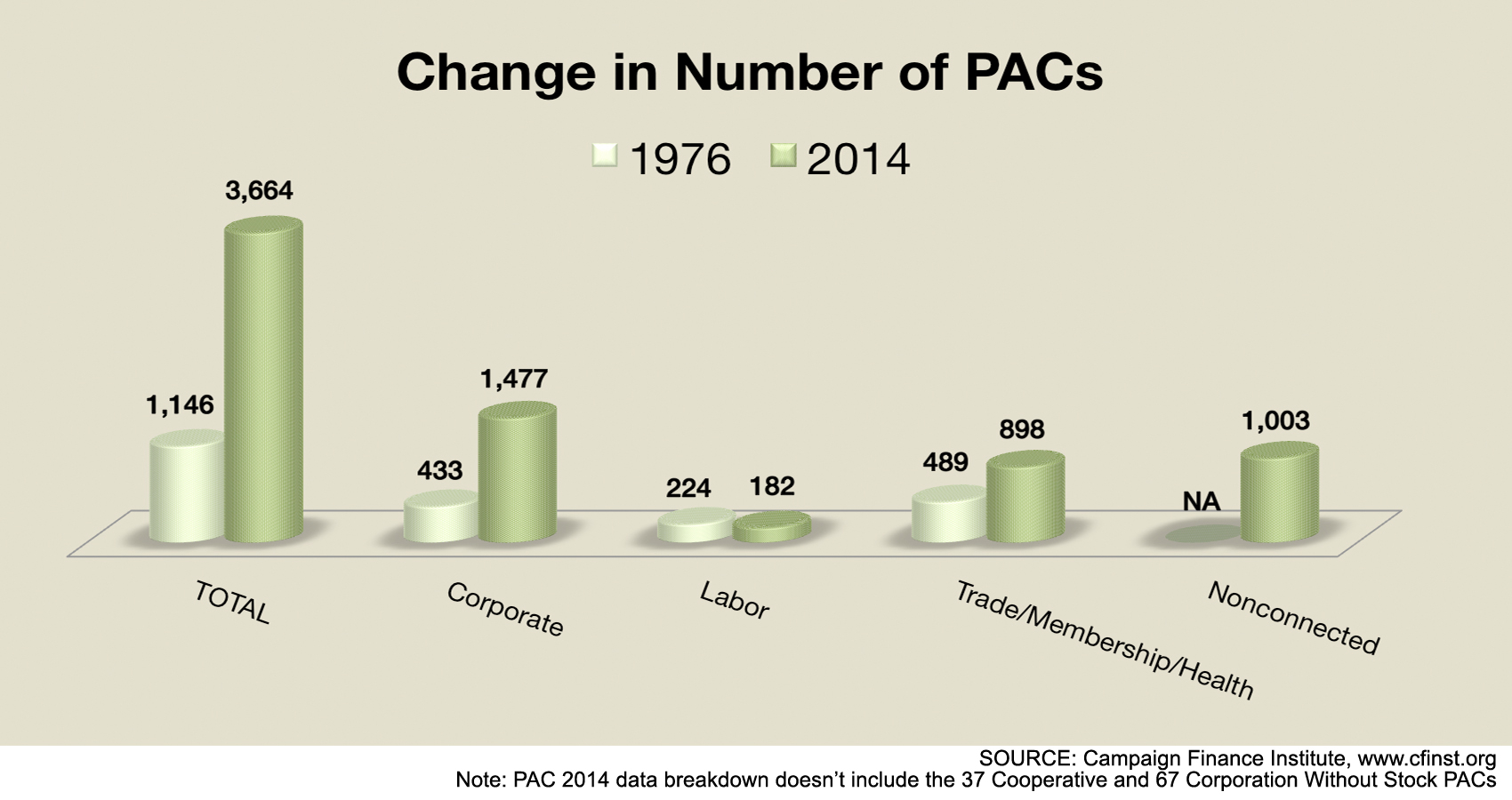

“Due to the diminishment of campaign financing reform by the Supreme Court,” explained T. Wayne Bailey, Ph.D., professor of political science at Stetson, “campaign financing is now in the hands of independent expenditure committees that operate outside of the regular campaign. For example, I can only contribute a certain amount to a federal candidate, but I can potentially create a Super PAC and raise hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

One such lucrative fundraiser was recently held in Daytona Beach, Fla., for prospective presidential candidate Jeb Bush, which raised “at least several hundred thousand dollars,” according to the Daytona Beach News-Journal. Because Bush has not yet declared his candidacy, there was no limit on what donors could give. The money officially goes to his political action committee.

Similarly, as reported by the Orlando Sentinel, Heathrow, Fla., attorney John Morgan, in conjunction with former president Bill Clinton, worked prolifically to earn money for various re-elections: two house parties “each raised more than $1 million; his first (Sen. Bill) Nelson (D-Fla.) party raised $250,000; and the (Sen. Elizabeth) Warren (D-Mass.) party raised $70,000.” Morgan also helped organize a fundraiser for President Obama at basketball star Vince Carter’s home that raised an estimated $2.1 million.

Similarly, as reported by the Orlando Sentinel, Heathrow, Fla., attorney John Morgan, in conjunction with former president Bill Clinton, worked prolifically to earn money for various re-elections: two house parties “each raised more than $1 million; his first (Sen. Bill) Nelson (D-Fla.) party raised $250,000; and the (Sen. Elizabeth) Warren (D-Mass.) party raised $70,000.” Morgan also helped organize a fundraiser for President Obama at basketball star Vince Carter’s home that raised an estimated $2.1 million.

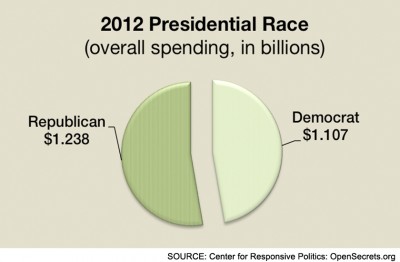

When it comes to wealthy donors, two of the most well known names include David and Charles Koch, controllers of Koch Industries, the second-largest, privately owned company in the U.S., earning revenue of $115 billion in 2013, says Forbes. As reported in The New York Times, the political network overseen by the Koch brothers plans to spend $889 million in campaign financing. That budget is potentially larger than either political party’s, and around 20,000 times the average annual income of U.S. citizens (about $45,000 in 2013, according to the Social Security Administration).

“I can’t even begin to imagine spending that much money,” said Bailey. “The Koch brothers’ influence is much greater than my influence or yours, because we don’t have access to that amount of resources. To mitigate this problem, if we can’t limit contributions, we should have transparency that will require disclosure of a donation’s origin, but under current law we may never know exactly who donated the money.

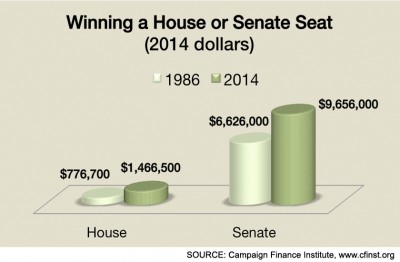

“If you are not wealthy or cannot attract wealthy donors, which is usually the case, you probably can’t win election to the office,” said Bailey. “One of the points that I make when I teach on this issue is that America is rapidly becoming a plutocracy, that is, a rule by the wealthy, in large part because of the reductions in campaign finance limitations.”

“In the American political system,” disagreed Congressman Gregg Harper (R-Miss) in an op-ed on his website, “private contributions have opened up new choices for candidates. In recent memory, it was private money that backed outlier candidates such as Ross Perot in 1992 and Ron Paul in 2008. It is the freedom to raise and spend money freely that has increased the likelihood of viable candidates.”

New Reformers

Laws in favor of campaign finance reform have been and still are being proposed by both parties. On the state level, Missouri state Sen. Rob Schaaf, a Republican, introduced major campaign finance reform legislation, the Missouri Anti-Corruption Act, which would overhaul the state’s campaign finance laws to empower average Missouri voters and reduce the influence of special interests, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. The bill would implement a small donor-based public financing system and measures to increase transparency and enforcement.

“The main difference between the large influence of the upper class and the influence of the individual boils down to money,” agreed former Florida state Rep. Joyce Cusack, a Democrat who serves as an At-Large Representative on the Volusia County Council. “We need to make sure that ordinary citizens have more opportunities when it comes to running for public office.”

Although many Republicans side with the Supreme Court’s decision, as Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) asserted in a Politico op-ed, a new group headed by conservative political consultant John Pudner called Take Back Our Republic is hoping to change that. It’s mission is “to alter the hostile posture of many Republicans toward new laws that would curb the reach of big-money donors, (and) to promote ‘market solutions’ to elevate the impact of small donors and advocate greater transparency for large political donations,” according to the Washington Post.

A Princeton University study by political scientists Gilens and Page found that even when there is a push by the general population for a specific change, that change rarely happens until businesses and elite classes are also behind it.

“What happens is that the people who can make or receive large contributions are ultimately the persons who are elected,” said Bailey. “The question is: what kind of laws are they going to pass? Well these are laws, in general, that provide breaks for the wealthy. And it’s the wealthy who already dominate the system.”

In a recent op-ed in The Huffington Post, Torres-Spelliscy cites three broad categories for laws that would allow an ordinary citizen a fighting chance in elections: “(1) rules that keep corporate money out of elections; (2) rules that govern pay-to-play, quid pro quo exchanges and (3) transparency rules for money in politics.”

Dark Money

While the Supreme Court tends to be in support of disclosure of donations, other problems can occur, such as the creation of “dark money.”

“There is a kind of clashing of cultures between the approach of the IRS and the approach of the FEC,” says Torres-Spelliscy, who teaches election law. “The FEC is supposed to provide transparency for the money that’s going through the electoral process. Meanwhile, the IRS keeps charities anonymous, whose primary purpose is not election-oriented.

“In order to have dark money in a federal election, a political spender, instead of spending up to the lawful limit, will go through a nonprofit and then the nonprofit will spend on their behalf,” Torres-Spelliscy said. “And because of pre-existing tax laws, certain nonprofits and charities remain anonymous. It becomes totally unclear from the point of view of the voting public that the original source of that money was either a specific individual or a specific corporation.”

“In order to have dark money in a federal election, a political spender, instead of spending up to the lawful limit, will go through a nonprofit and then the nonprofit will spend on their behalf,” Torres-Spelliscy said. “And because of pre-existing tax laws, certain nonprofits and charities remain anonymous. It becomes totally unclear from the point of view of the voting public that the original source of that money was either a specific individual or a specific corporation.”

An argument against disclosure laws is that they violate privacy. About privacy versus transparency, Aldous Huxley said: “The survival of democracy depends on the ability of large numbers of people to make realistic choices in the light of adequate information. A dictatorship, on the other hand, maintains itself by censorship and distorting the facts, and by appealing, not to reason, not to enlightened self-interest, but to passion and prejudice.” We must ask ourselves: Does disclosure, in this case, help or harm democracy?

“Even if you have a corporation that’s being transparent,” added Torres-Spelliscy, “you have a different problem, which is that shareholders in the United States aren’t given the opportunity to approve that political spending. And this stands in contrast to the United Kingdom. In the U.K., shareholders in British companies get the opportunity to accept or reject a budget.”

The consequence of inaction on campaign finance laws might be the replacement of the individual by the dollar, but can anything be done without infringing on freedom of speech? As Alexander Heard, who was appointed Chancellor of Vanderbilt University from 1963 to 1982, told Bailey when they studied American politics many years ago, “campaign finance is the Achilles’ heel of American democracy.”

George Salis is a student writer for Stetson Today.