Researcher Helps Florida Cities Adapt to Sea-Level Rise

Increased flooding caused by sea-level rise is a growing threat to the homes and businesses in coastal cities around Florida. Satellite Beach, a small town on Florida’s Space Coast filled with ocean-loving surfers and anglers, is no exception.

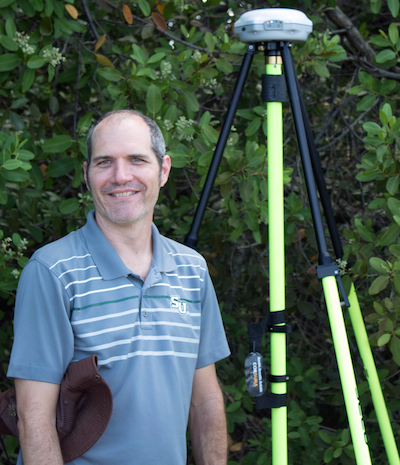

In response to the problem, Jason M. Evans, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental science and studies at Stetson University, is finding ways for local governments in several cities, including Satellite Beach, to best adapt to sea-level rise. Part of Evans’ research, which is funded by the Florida Sea Grant program, is mapping how vulnerable public facilities such as stormwater drainage systems, fire stations and wastewater treatment plants are to rising seas.

The elevations of the structures that Evans records give him insight into how exposed buildings can be adapted for future floods. He hopes this data will help communities become more resilient to coastal hazards.

“Resiliency is the idea that a community can bounce back from some kind of stressor, some kind of disaster,” Evans said. “With sea-level rise, the best thing we can do is just acknowledge it and try to deal with it by planning ahead.”

The research Evans and his team recently published in the prestigious journal Nature Climate Change found that as many as 13.1 million Americans who live in low-lying coastal areas would be displaced due to sea-level rise by 2100.

“It’s basically a collision course when thinking about sea-level rise,” Evans said in an on-air interview with the popular radio show Science Friday. “We’re starting to do studies that say, OK, how much is it going to cost to adapt?”

Evans hopes the data he collects in Satellite Beach will reduce flood insurance costs for property owners in some less-vulnerable areas.

“What this work will ideally do is show communities how to use the Community Rating System (CRS) as a way of planning for sea-level rise,” Evans said, referring to the National Flood Insurance Program’s method of encouraging a community to go above and beyond minimal flood-plain strategies.

The higher “resilience” score a community achieves through the CRS, the lower the flood insurance rates are across the board for that community. These savings will make sea-level rise seem less controversial, according to Evans.

“For communities that are following the Community Rating System practices there is a real potential to help people save a little bit of money on their flood insurance. And that’s a tangible benefit in the very near term,” Evans said.

Once data collection is complete, Evans will report his findings to the city manager and public works director of Satellite Beach. Local officials can then use the findings to improve flood hazard and infrastructure planning that earns Satellite Beach additional credits on the CRS.

“I think the reaction that we would like to get from the community is that we’re trying to solve actual problems,” Evans said. “They already have flooding issues in Satellite Beach. We know there is such a thing as sea-level rise because we see it and we can measure it.”

Evans’ research in Satellite Beach will be one of the first projects conducted at Stetson’s Institute for Water and Environmental Resilience. The institute focuses on research that will offer policy options to protect water in Central Florida and beyond.

Pictured in the photo on front page of Stetson Today are (l to r): Holly Abeels, George Wintson, Nick Gastesi, Emily Niederman, Evans and John Fergus.

By Rhiannon Boyer